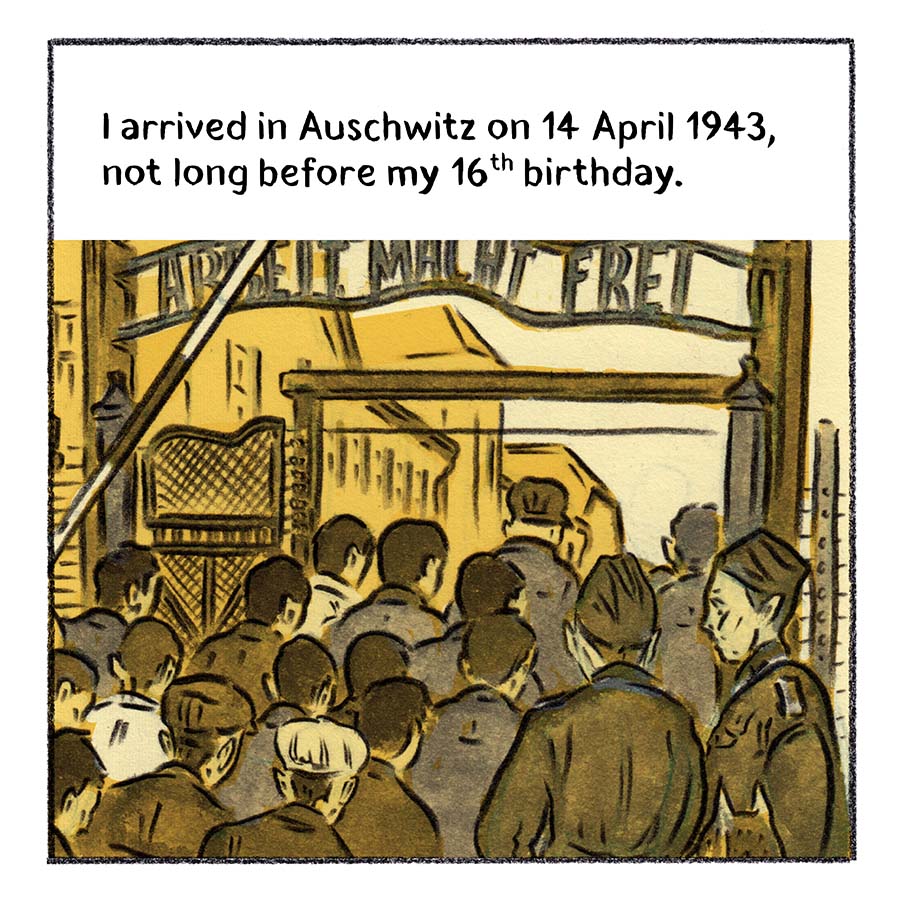

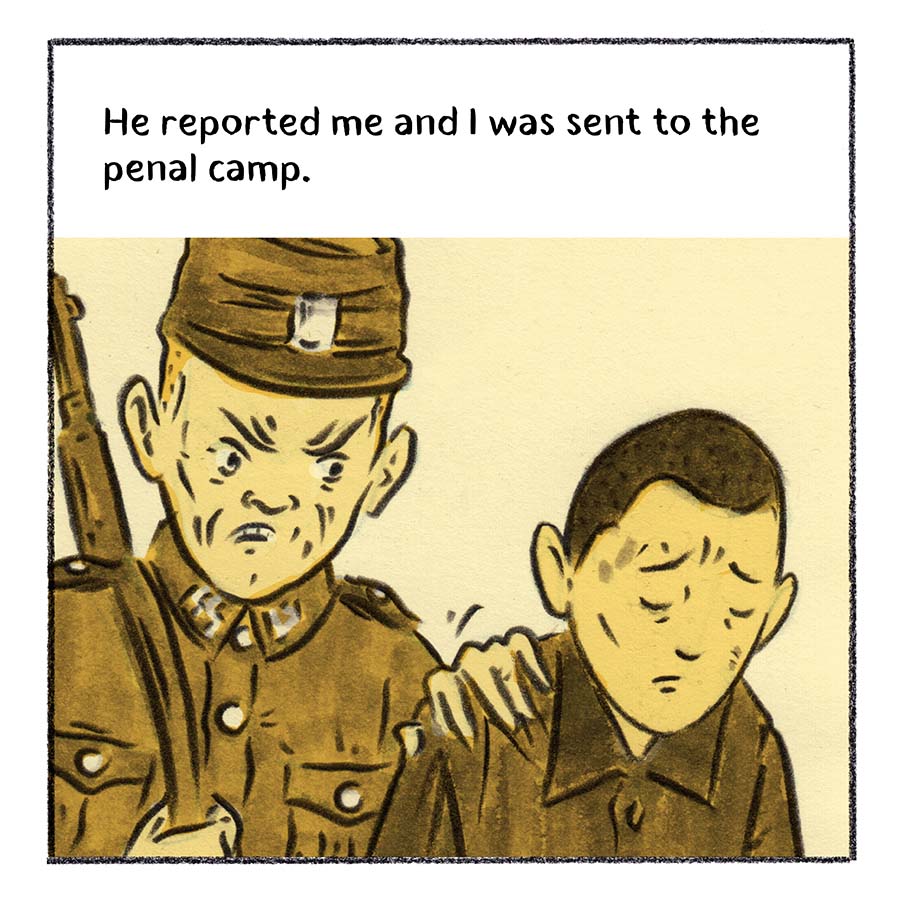

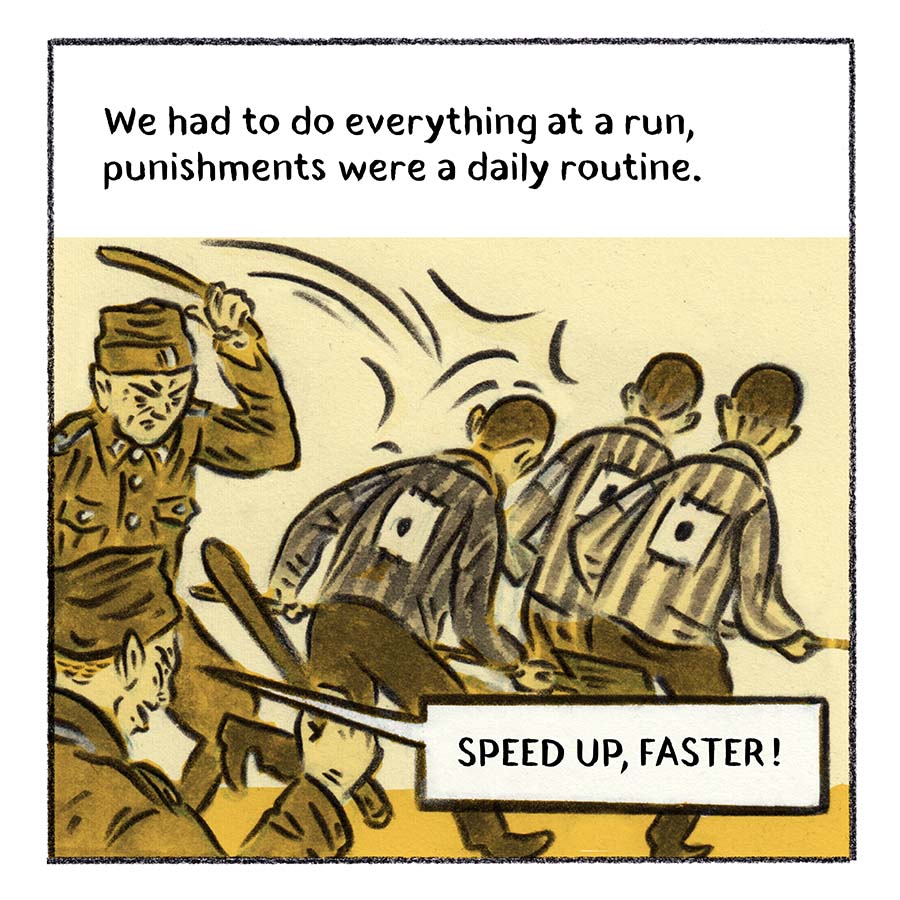

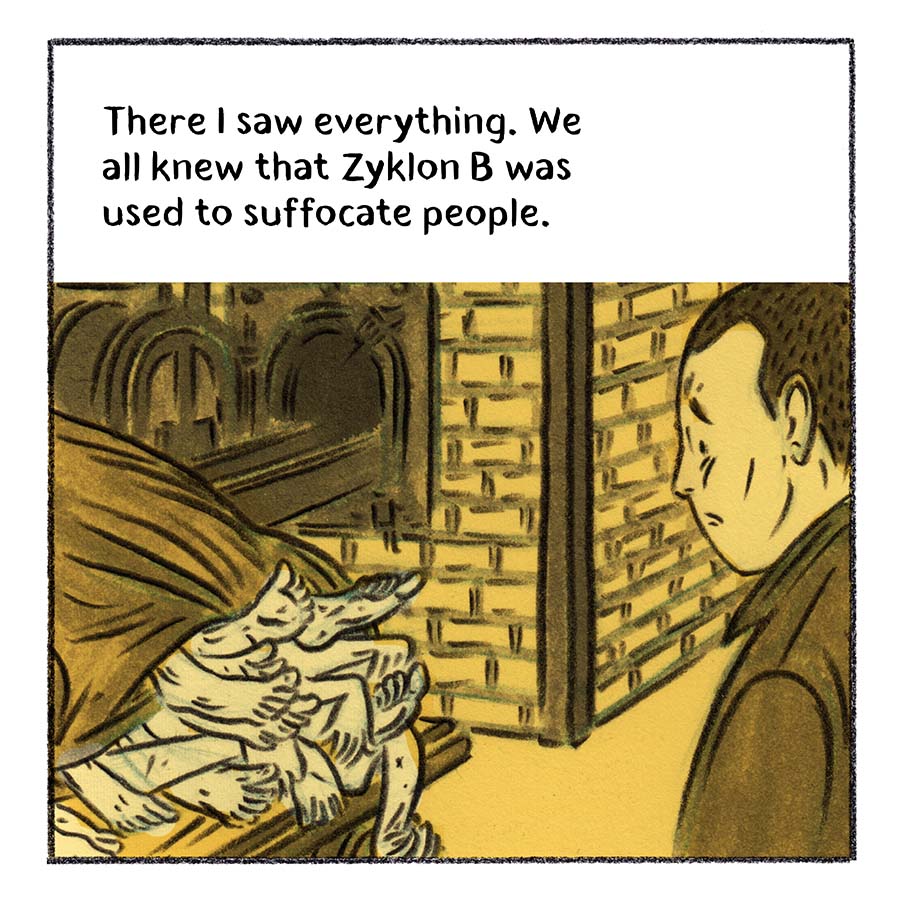

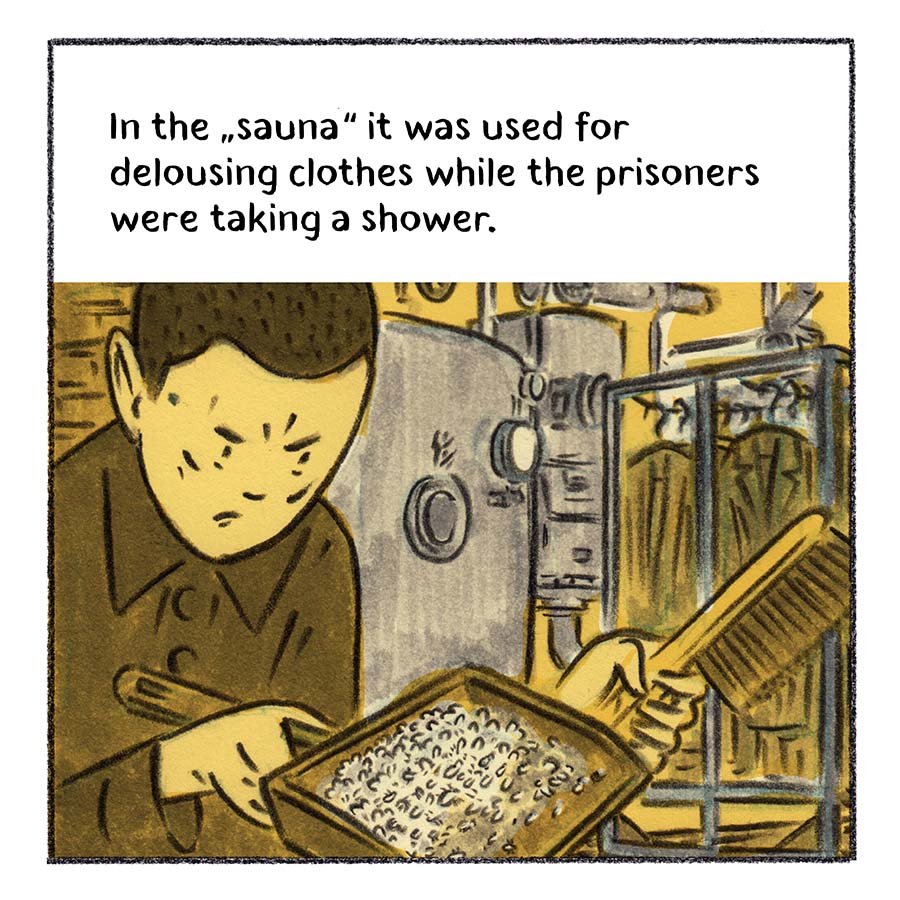

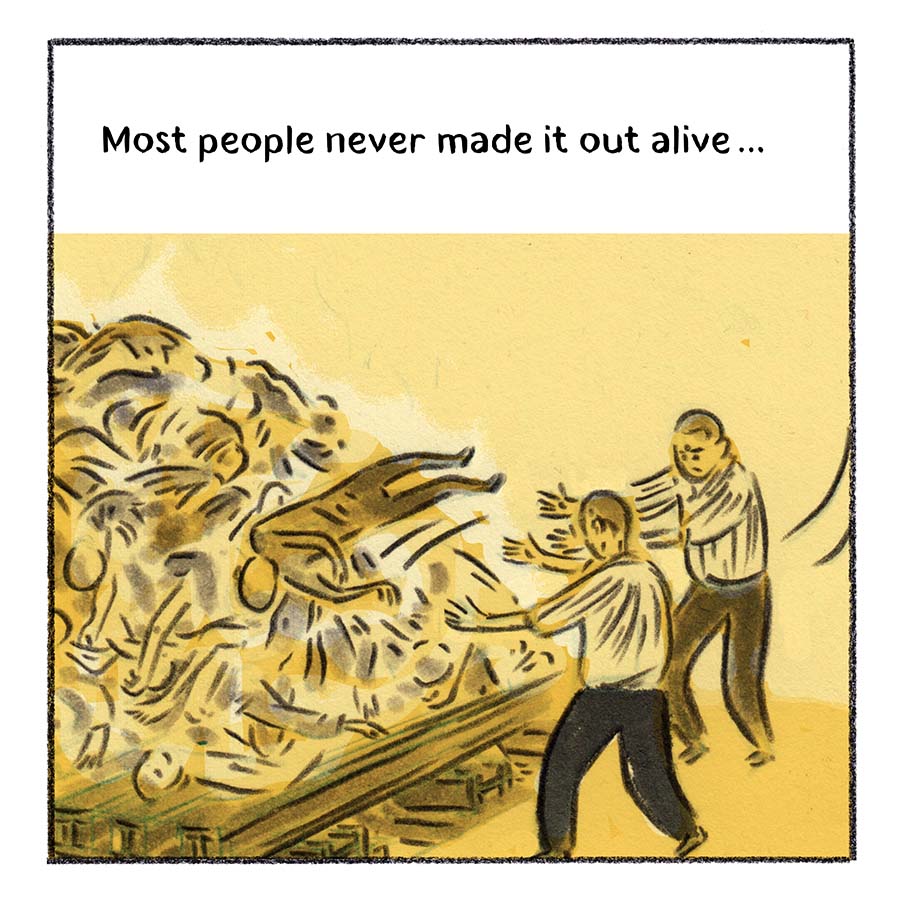

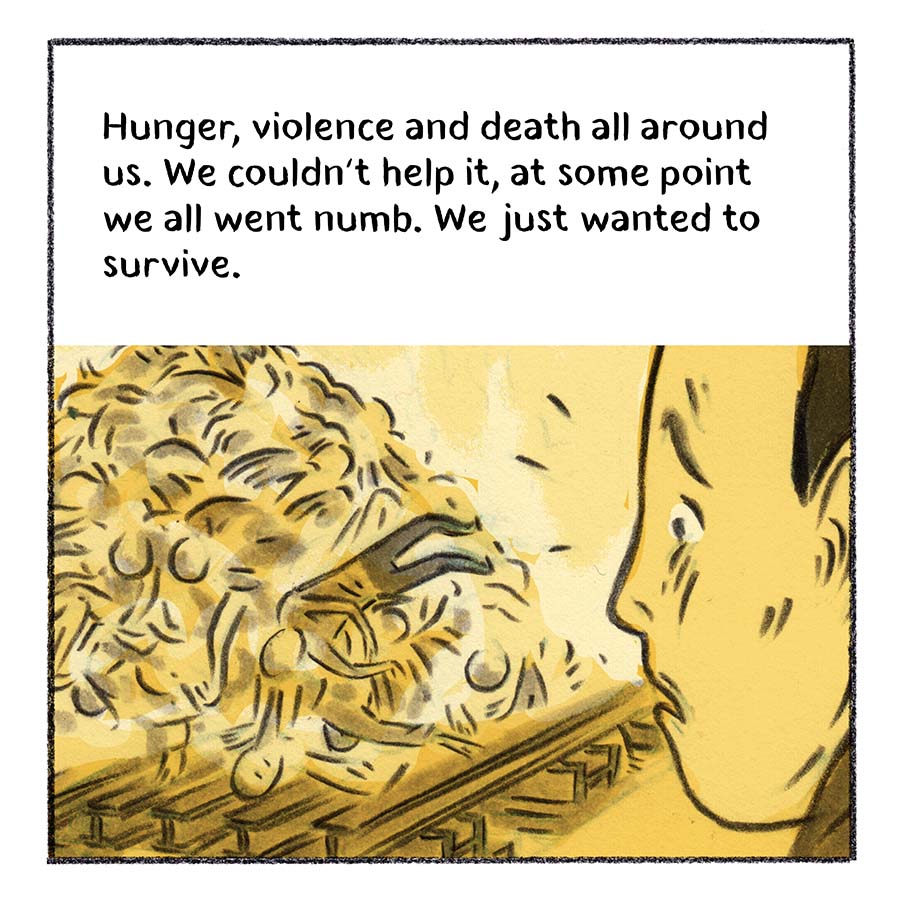

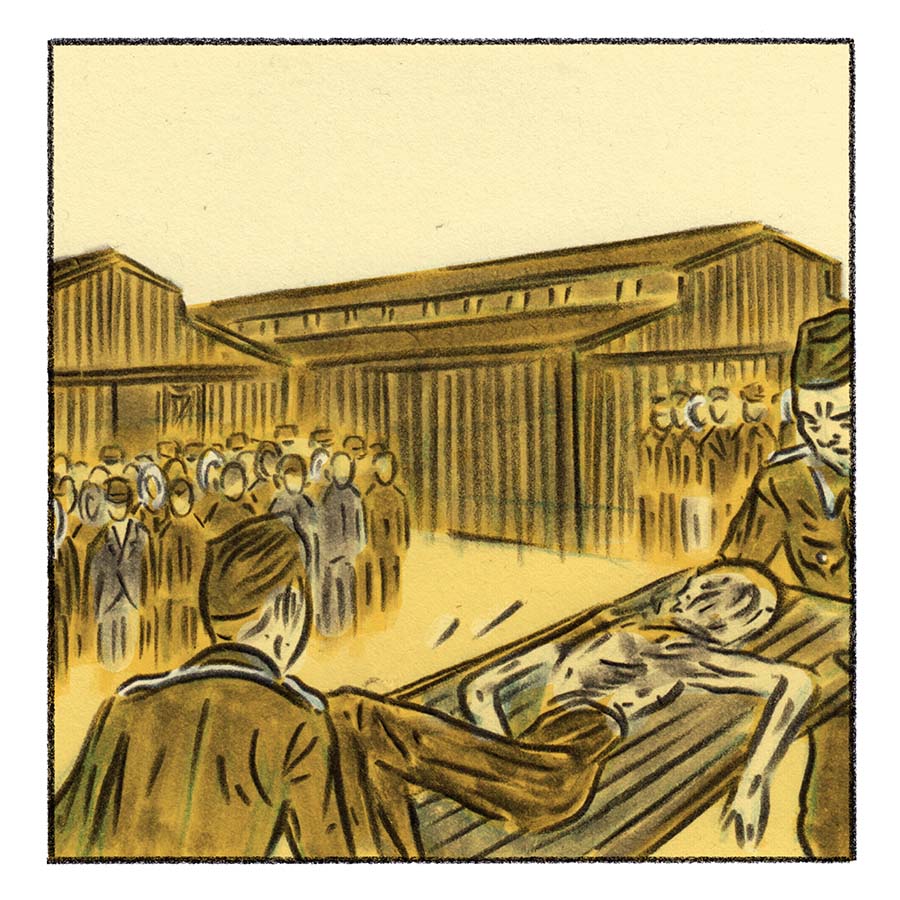

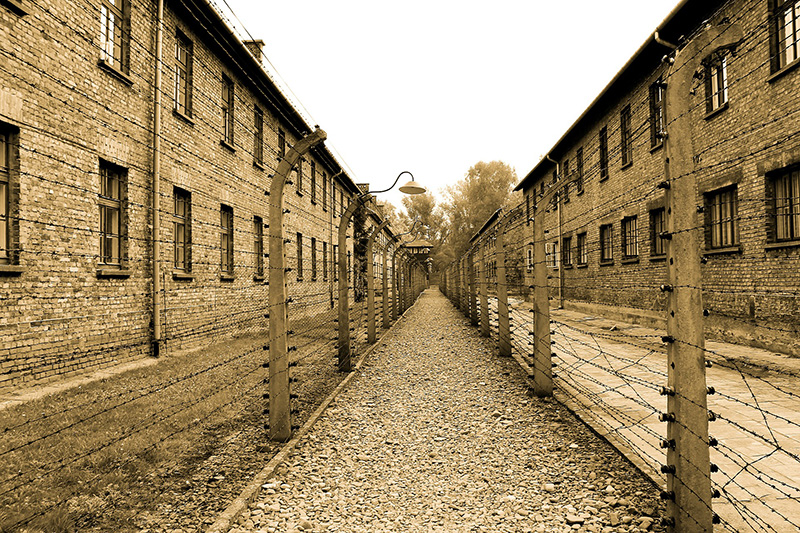

Auschwitz was the largest concentration and extermination camp in Nazi Germany. Over one million people were murdered in Auschwitz, most of them Jews. But political opponents, Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, priests and people with disabilities also became victims of the Nazi extermination strategy. The camp was built in 1940 in a former barracks in the town of Oświęcim, initially for Polish prisoners. In nearby Birkenau, a camp for 100,000 prisoners of war was to be built in 1941. However, Birkenau did not serve this purpose, it rather became the killing centre were millions of people were murdered. In addition to the Auschwitz I main camp and the extermination camp Birkenau Auschwitz II, including the so-called Auschwitz Gypsy camp, the Auschwitz camp complex also included the Auschwitz III camp (Monowitz) next to the construction site of a huge I.G. Farben chemical factory. Beginning in the summer of 1942, Jews deported almost from all over Europe were "selected" according to their ability to work upon arrival in Birkenau. Only persons registered as prisoners were given a number; all others were immediately killed in the gas chambers. By the summer of 1944, the Reich Security Main Office had deported 1.1 million Jews to Birkenau, of whom about 900,000 had been murdered immediately. About 20,000 Sinti and Roma also died from the devastating conditions in the "Gypsy camp" or were gassed. As the Soviet army approached, the SS began burning files, death certificates and other evidence of their crimes, as well as blowing up barracks, gas chambers and crematoria. On 27 January 1945, the Soviet army freed 7,000 terminally ill prisoners - tens of thousands more had been driven west by the SS on "death marches" before the Red Army arrived. In 1963, the "Auschwitz Trial" against 22 guards began in Frankfurt/Main. A total of 359 witnesses from 19 countries were heard in court, mostly former prisoners. After 154 trial days, the court sentenced six of the defendants to life imprisonment. The former commandant Rudolf Höß had already been sentenced to death and had been executed in Poland in 1947. The sentences were often criticised as too lenient, but the Auschwitz trials started a society-wide debate on how to deal with Nazi crimes and one's own complicity. In 1979, the statute of limitations for murder was lifted in the Federal Republic of Germany so that prosecution of the perpetrators could continue. As of 2011, it is also possible to prosecute people who, through their work, have become accessories to the Nazi crimes.

Entrance of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp

Bundesarchiv, B 285 Bild-04413 / Stanislaw Mucha / CC-BY-SA 3.0

© Stanislaw Mucha, 1945

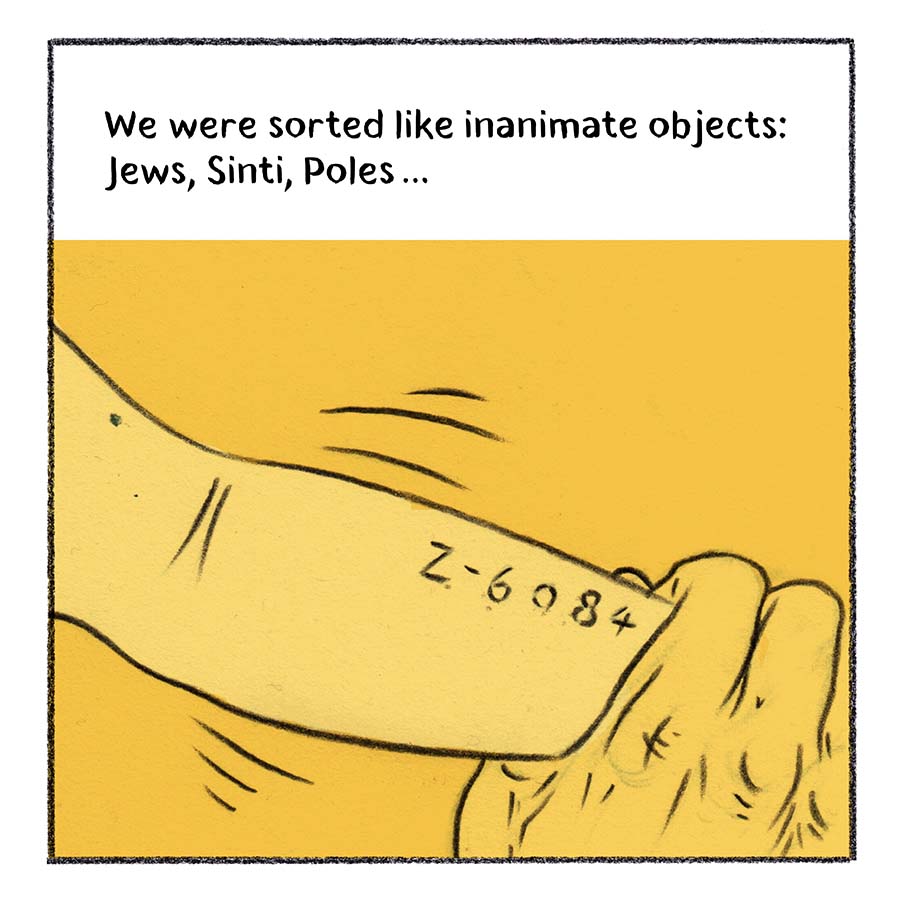

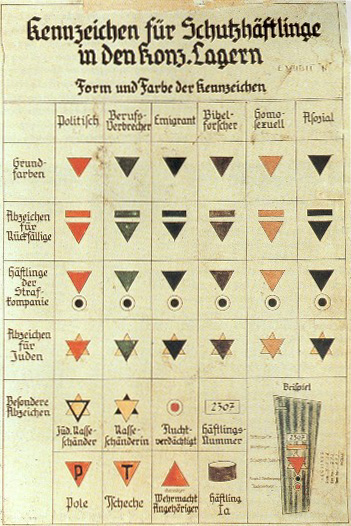

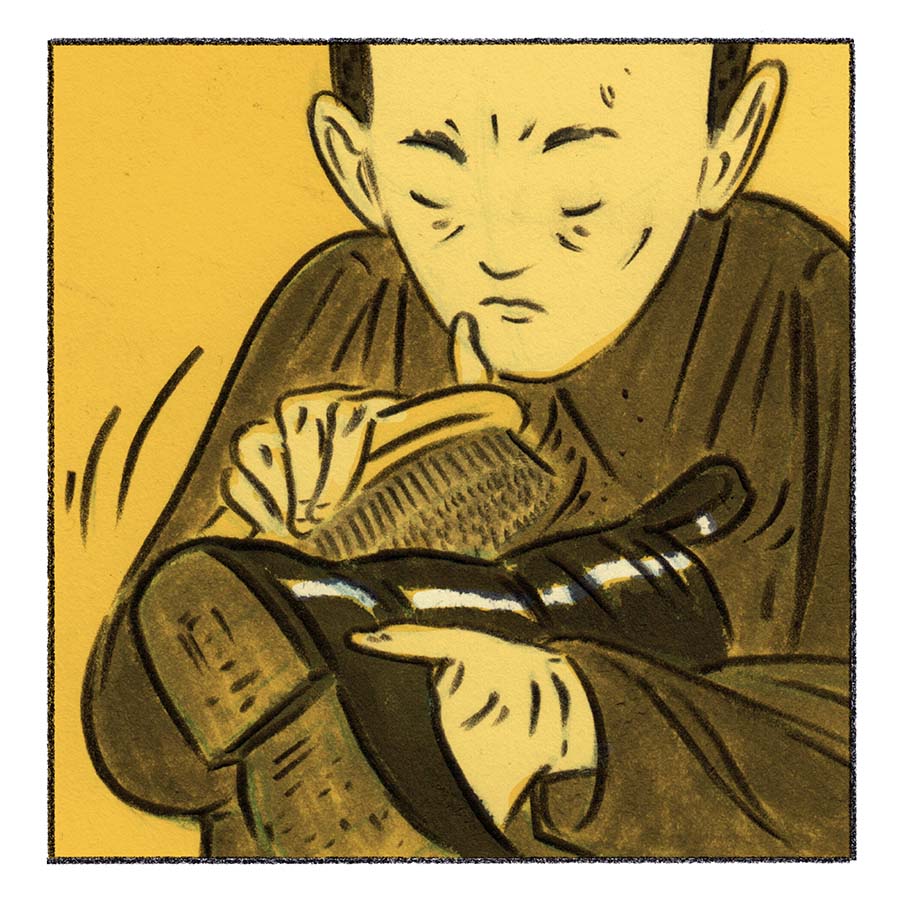

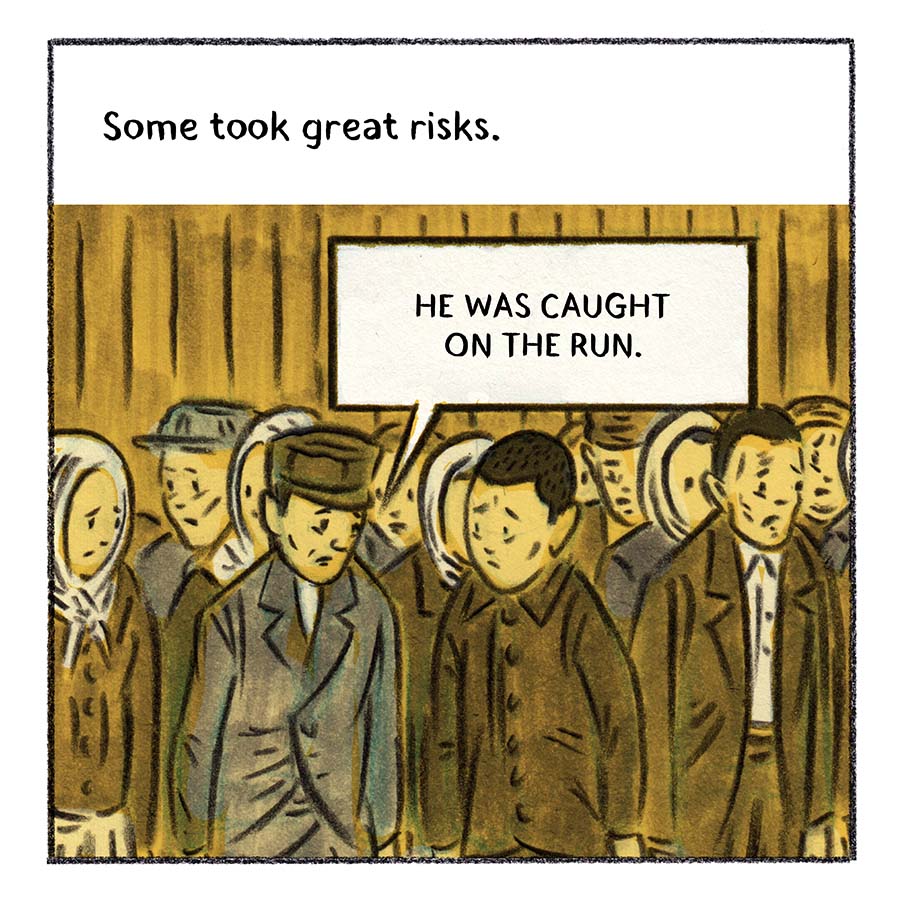

The SS divided concentration camp prisoners into different prisoner groups and labelled them accordingly. This helped guards to recognise which group they belonged to. Classification was based on nationality, ascribed "race" and categories introduced by the SS such as "asocials" or "professional criminals" and was visualised by means of coloured fabric triangles sewn onto the prisoners' clothing. Other labels were used to indicate who was serving the SS as a prisoner functionary (e.g. room elder, block elder or barrack elder). Prisoners could therefore belong to more than one prisoner group, and accordingly several labels were combined on their clothing. In addition to those labels, Auschwitz concentration camp inmates had a number tattooed on their body. This was to help quick identification in case of escape attempts and also to prevent the misidentification of undressed corpses.

Identification of inmates in Nazi concentration camps from the early 1930s.

© United States Holocaust Museum, Washington, erstmals veröffentlicht 2006

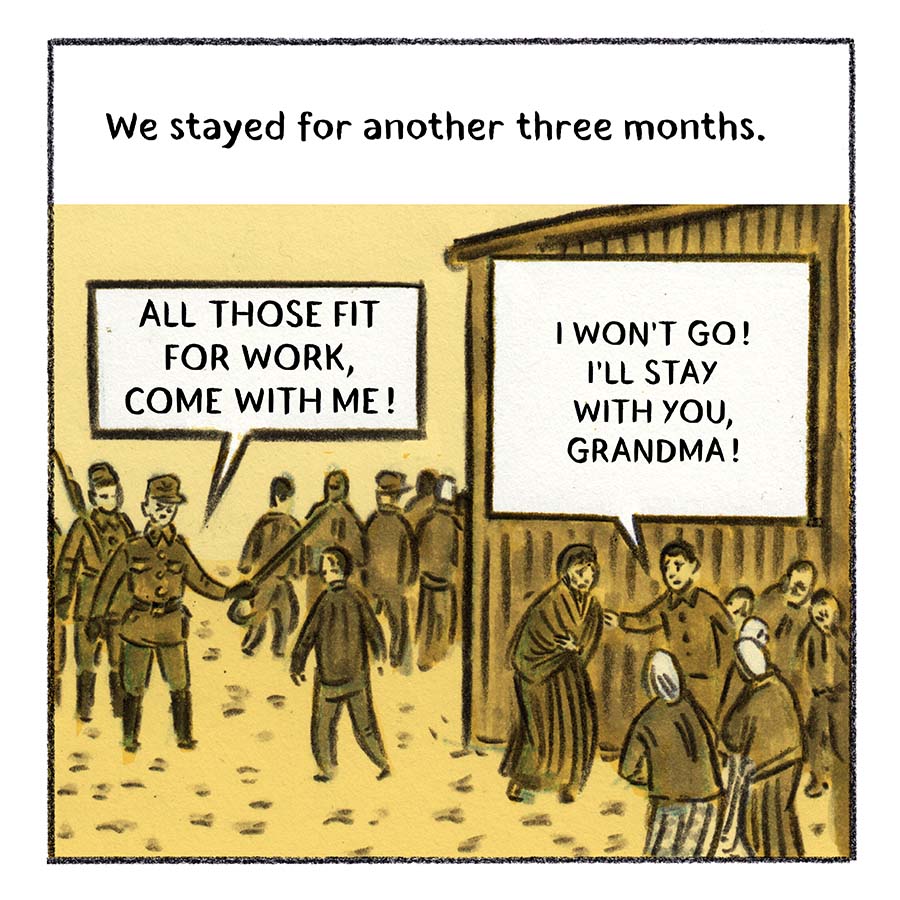

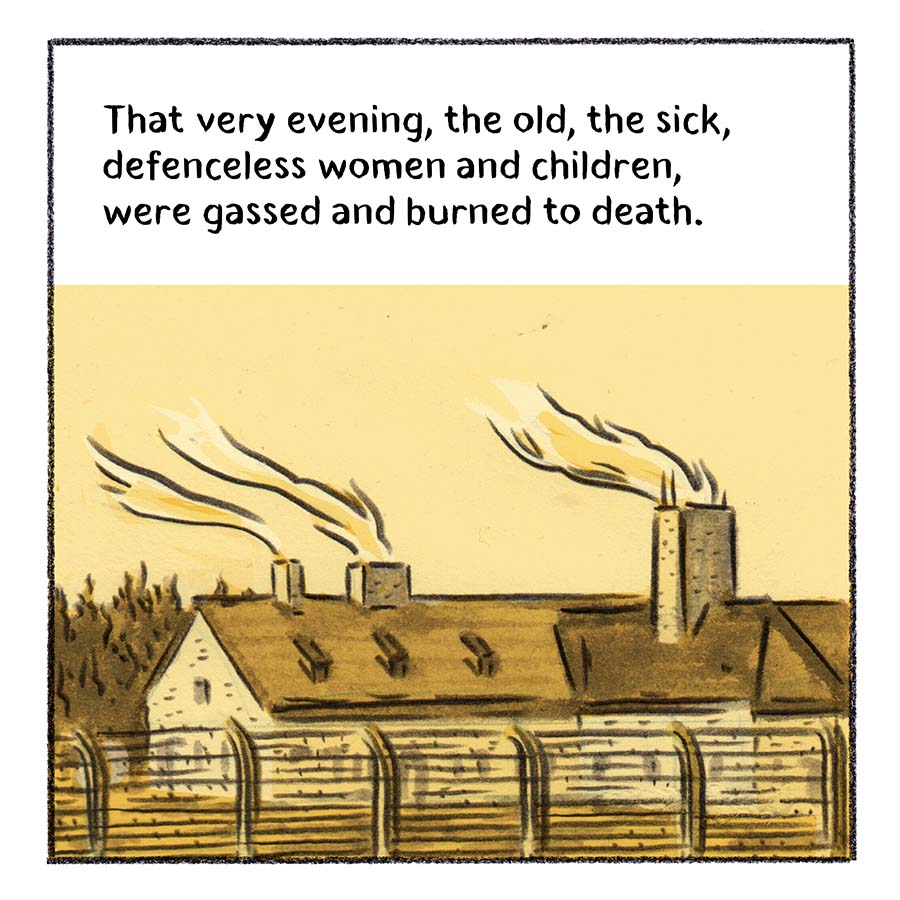

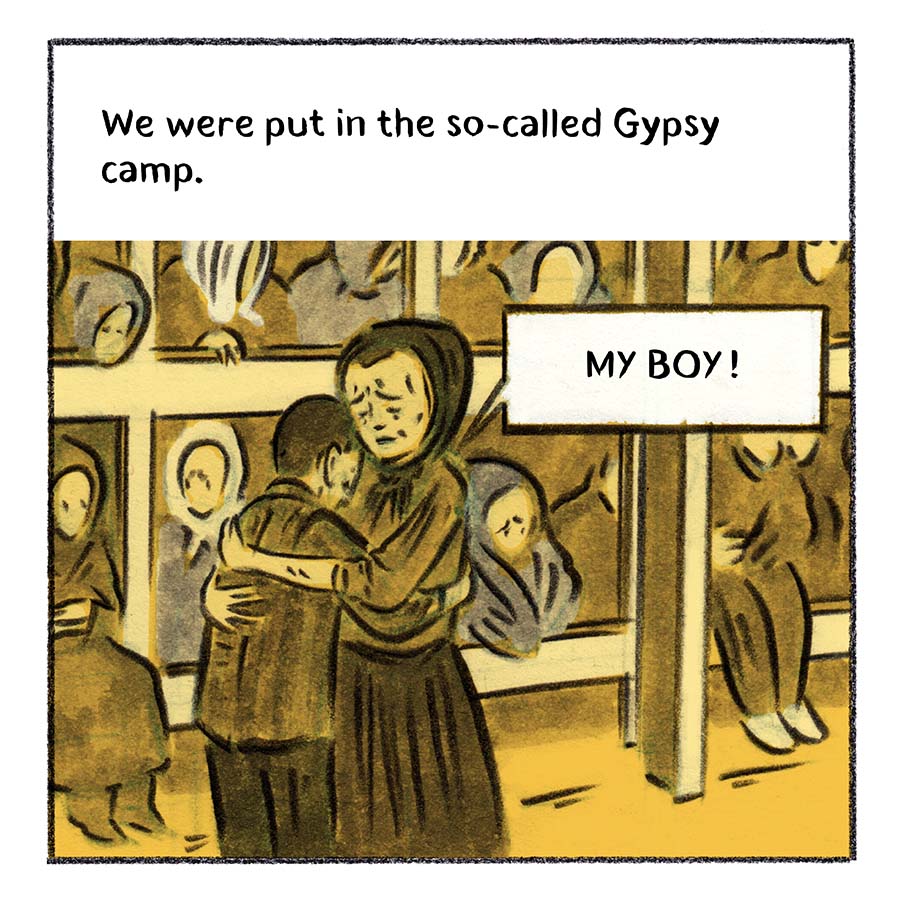

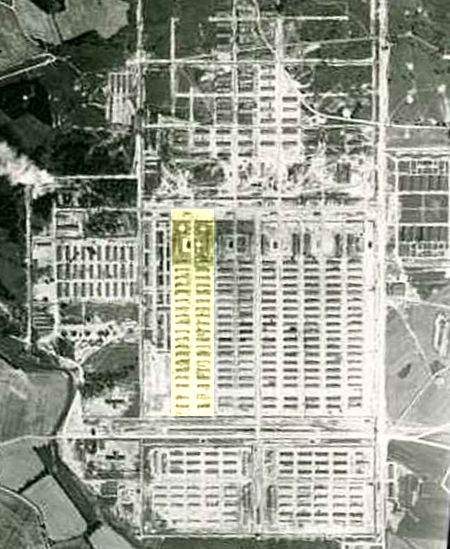

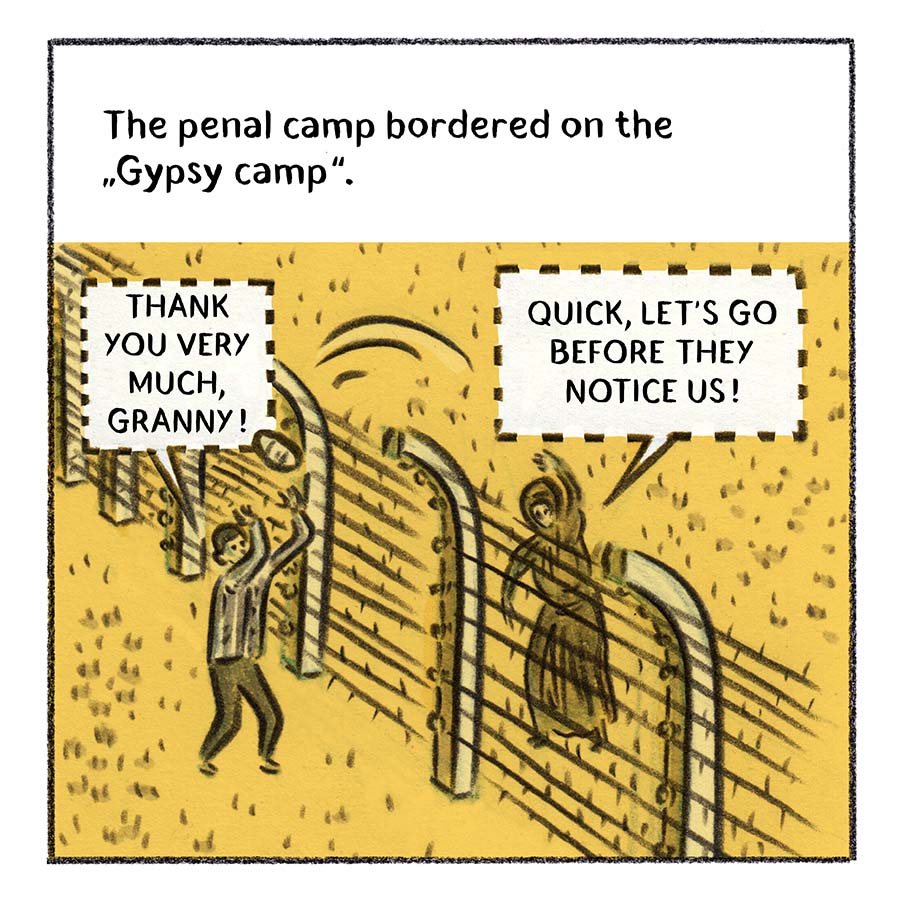

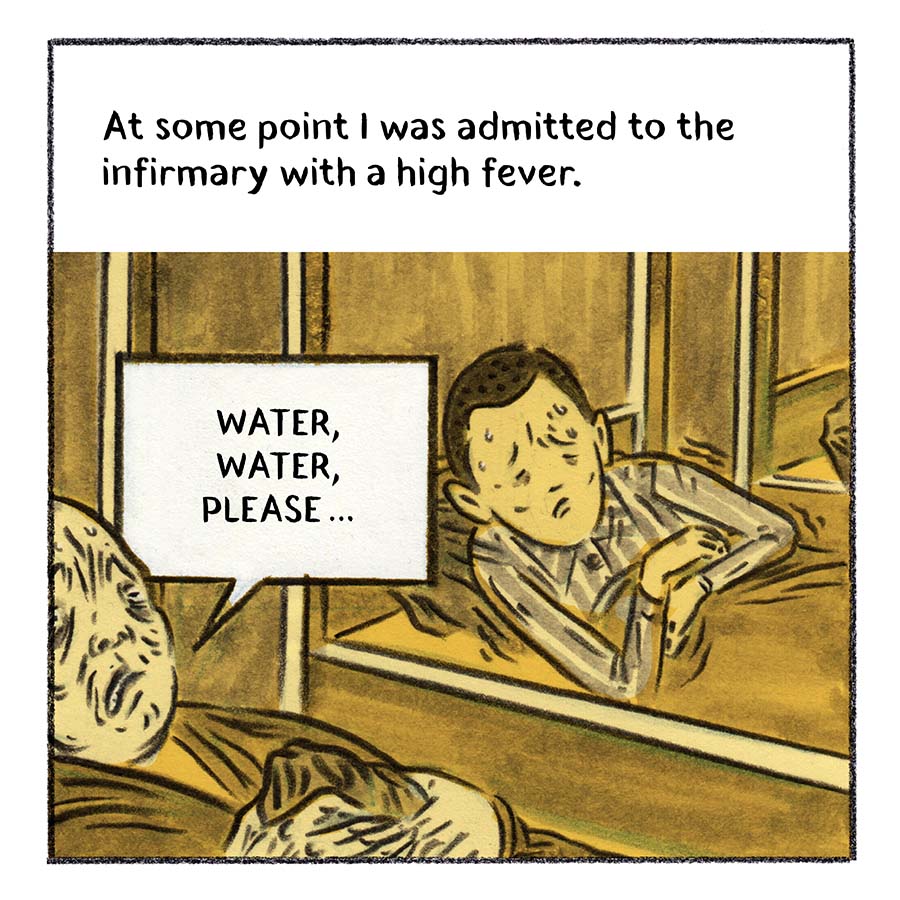

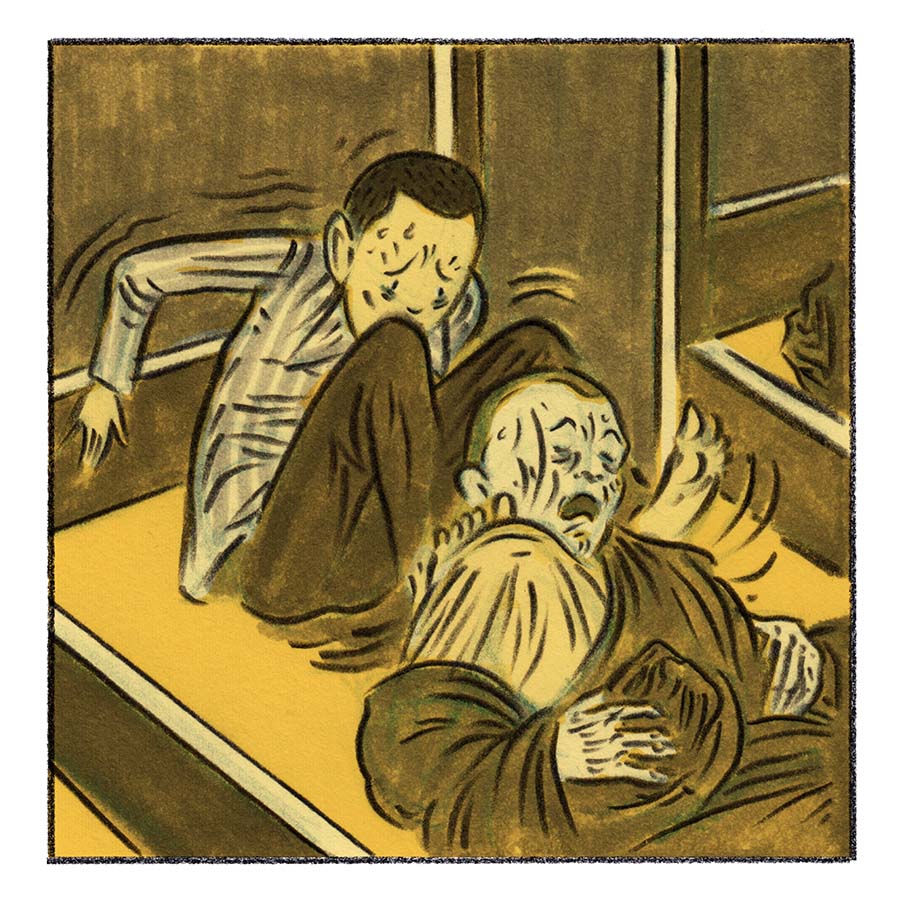

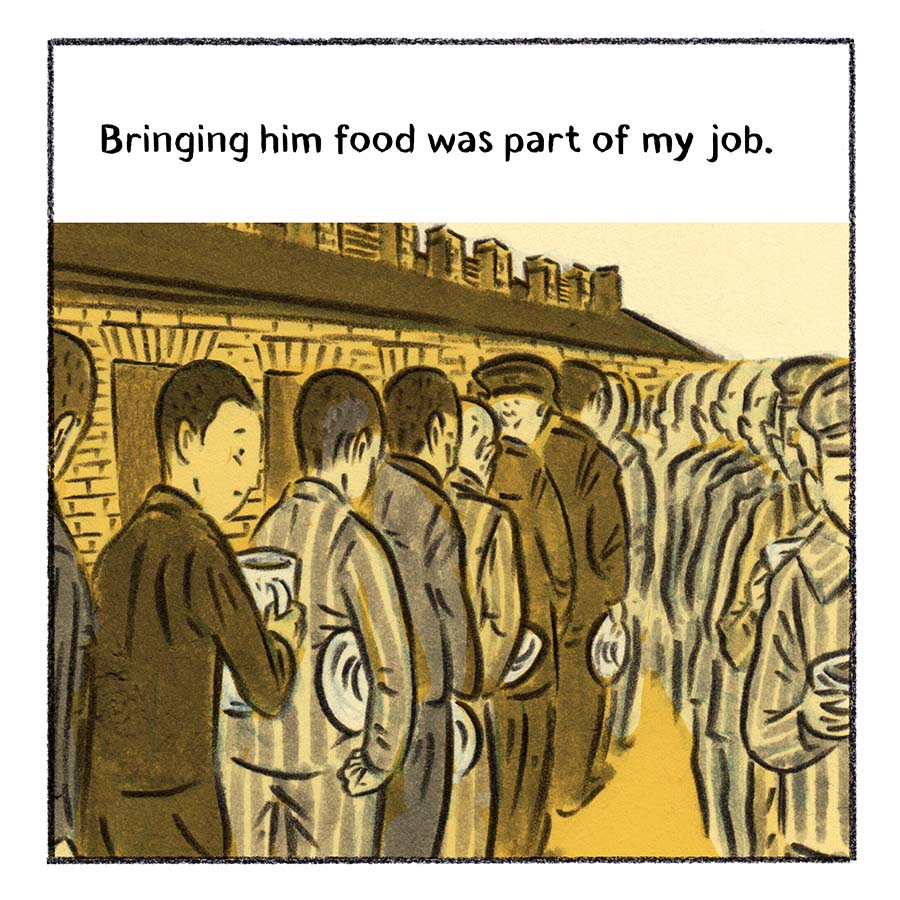

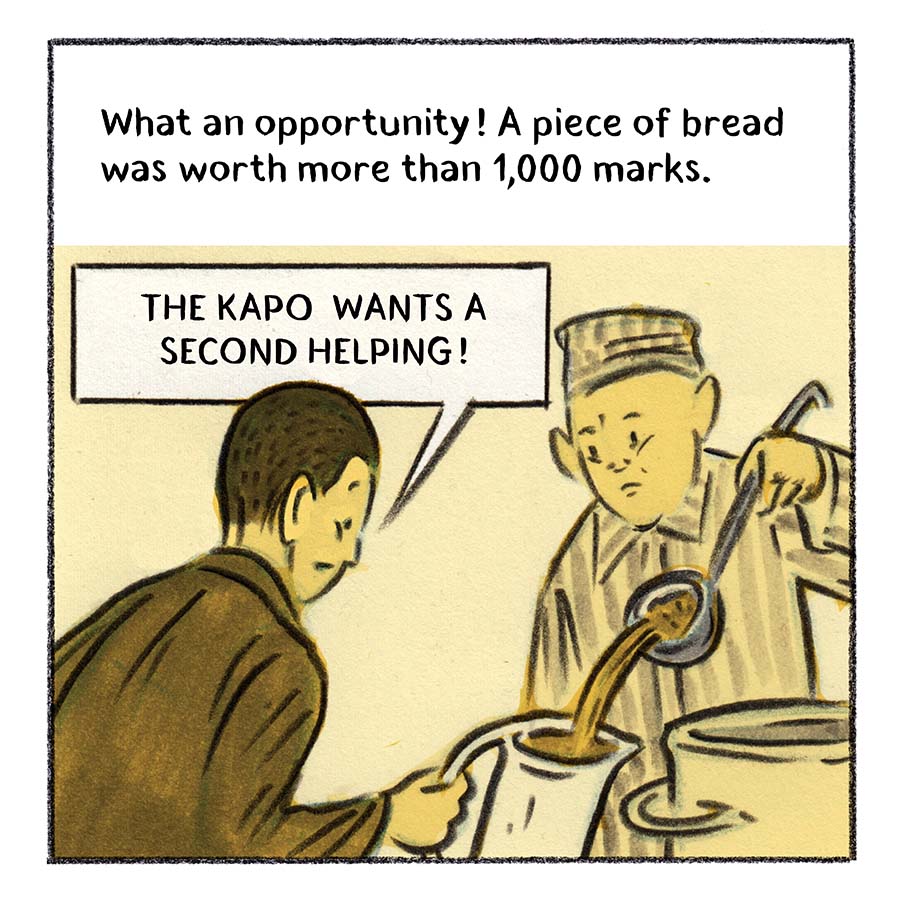

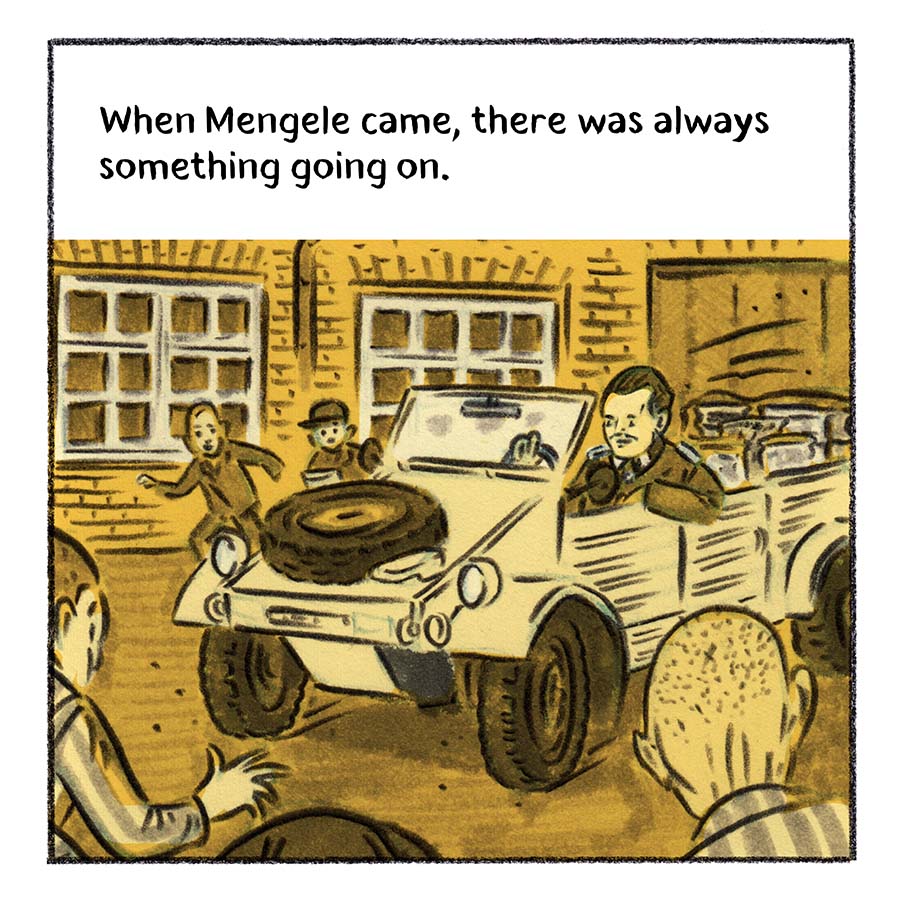

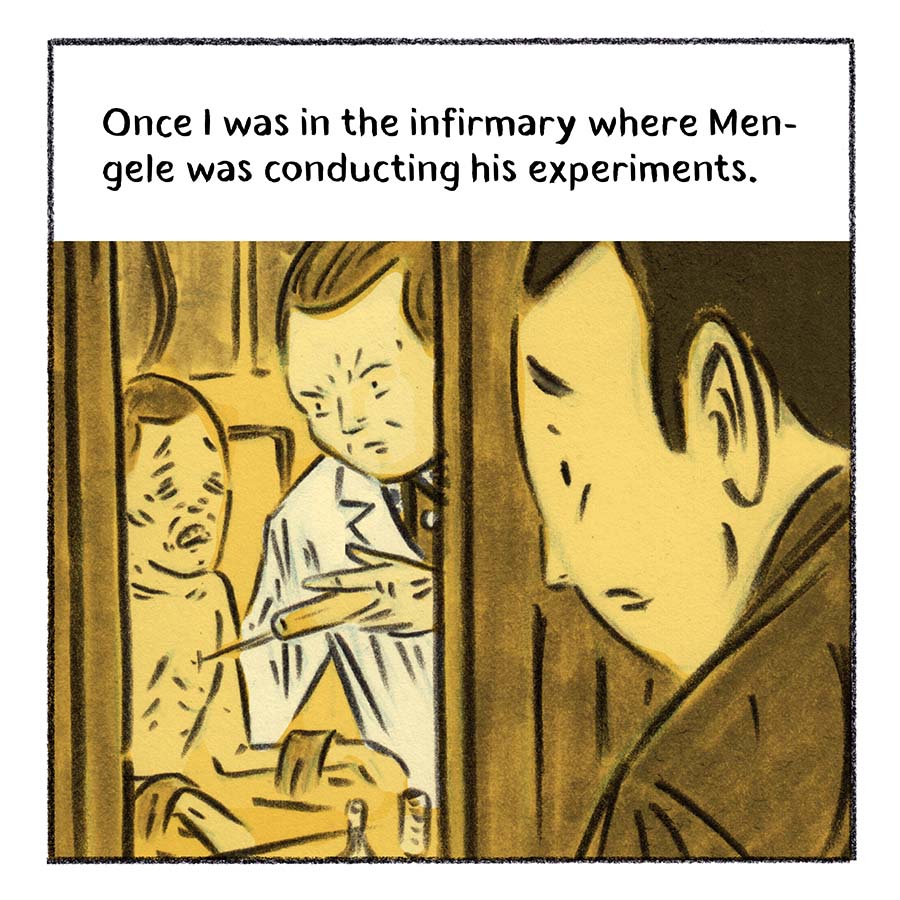

The so-called Gypsy camp refers to Section II B e of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and was built in December 1942 on Himmler's orders. It consisted of 32 non-insulated wooden barracks of the "horse stable" type. Although the barracks were designed for only 400 people each, sometimes up to 1,000 prisoners were literally crammed into them. Even larger families were only given one cot. In contrast to other camp sections, men, women and children were not accomodated separately here. They also kept their civilian clothes - also contrary to common practice in Auschwitz. Complete overcrowding in the barracks, inadequate food supplies and heavy physical work led to mass outbreaks of diseases and death. The camp for Sinti and Roma also gained notoriety for the "pseudo-scientific" experiments of camp physician Josef Mengele. On 16 May 1944, there was an uprising in the "Gypsy camp". Armed with stones and tools, the prisoners barricaded themselves in order to prevent the liquidation of the camp. On 2 August 1944, the SS liquidated the camp and murdered the remaining almost 3,000 Sinti and Roma, including many elderly people and children. In total, more than 23,000 Sinti and Roma had been deported to the "Gypsy camp" in Auschwitz-Birkenau between 26 February 1943 and 1 August 1944.

The "Gypsy Camp" in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp

© British Government, 1944

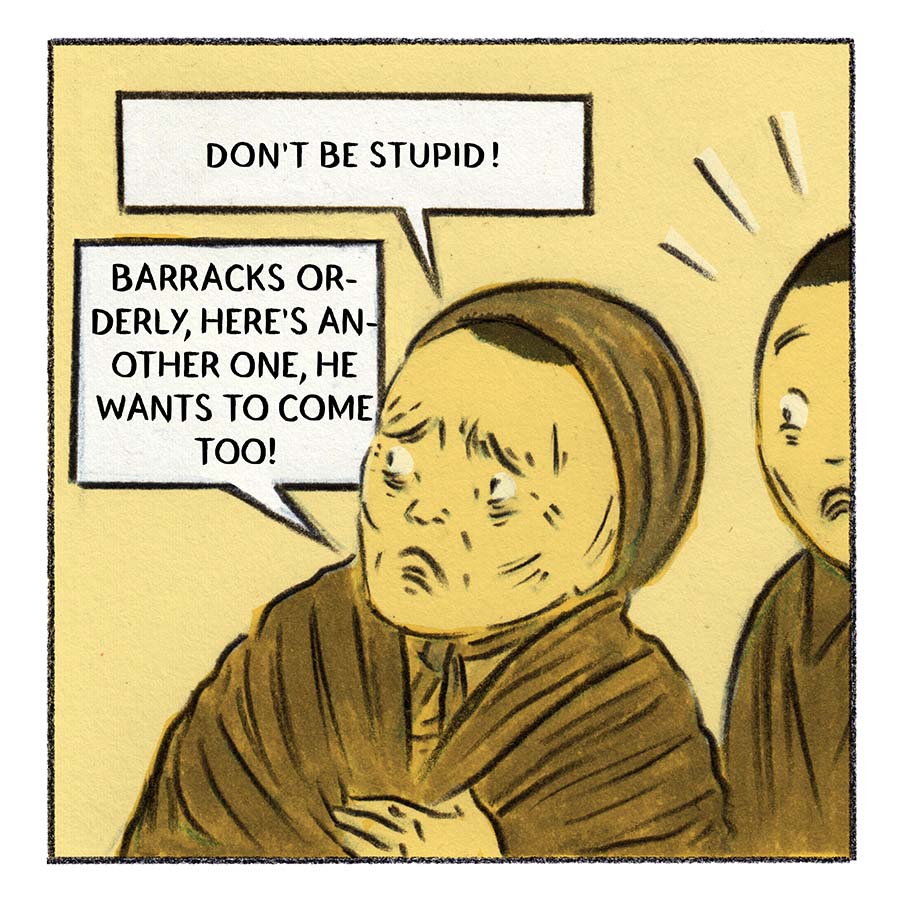

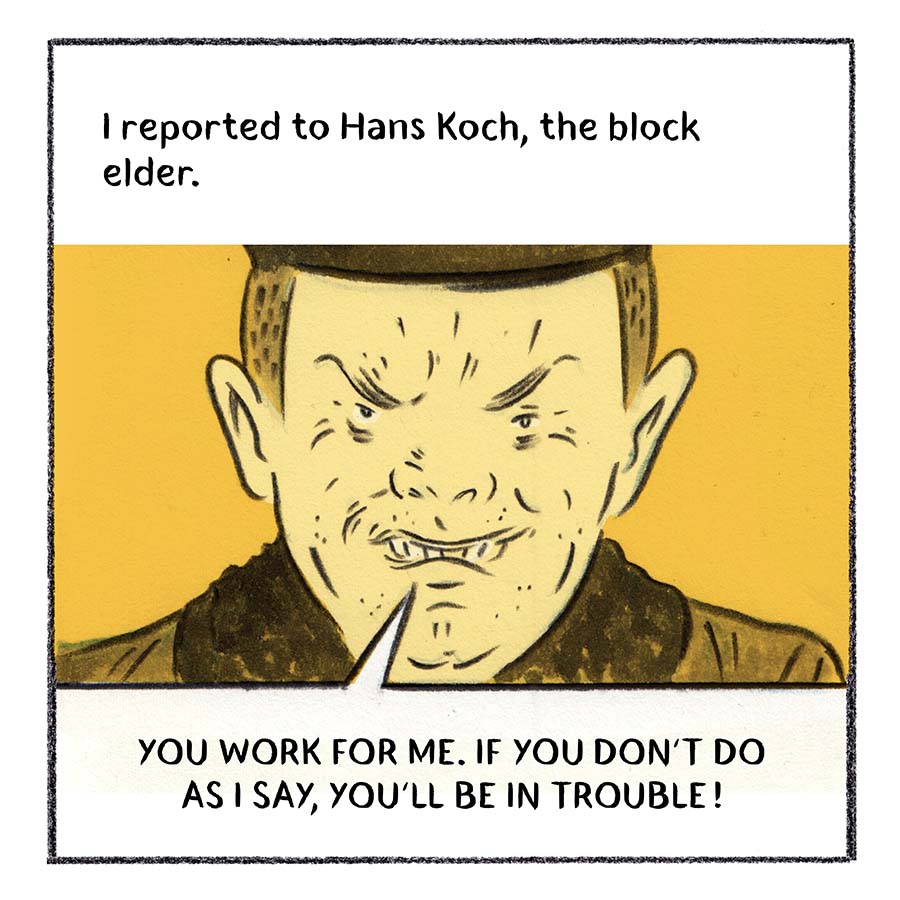

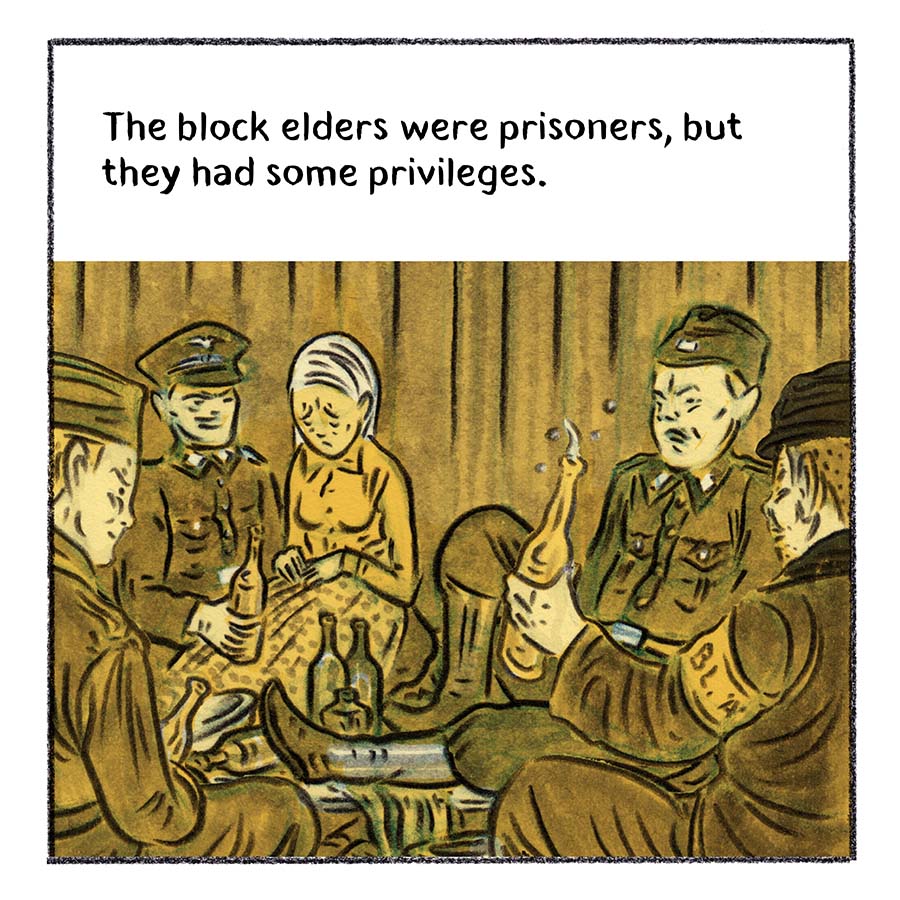

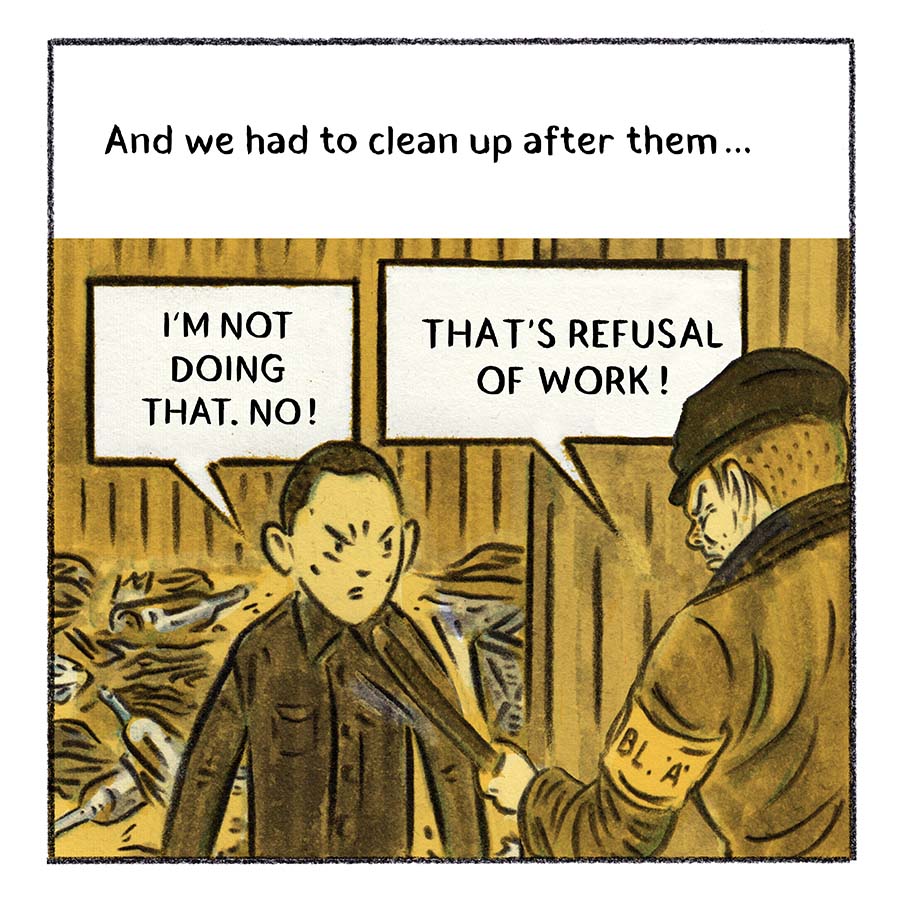

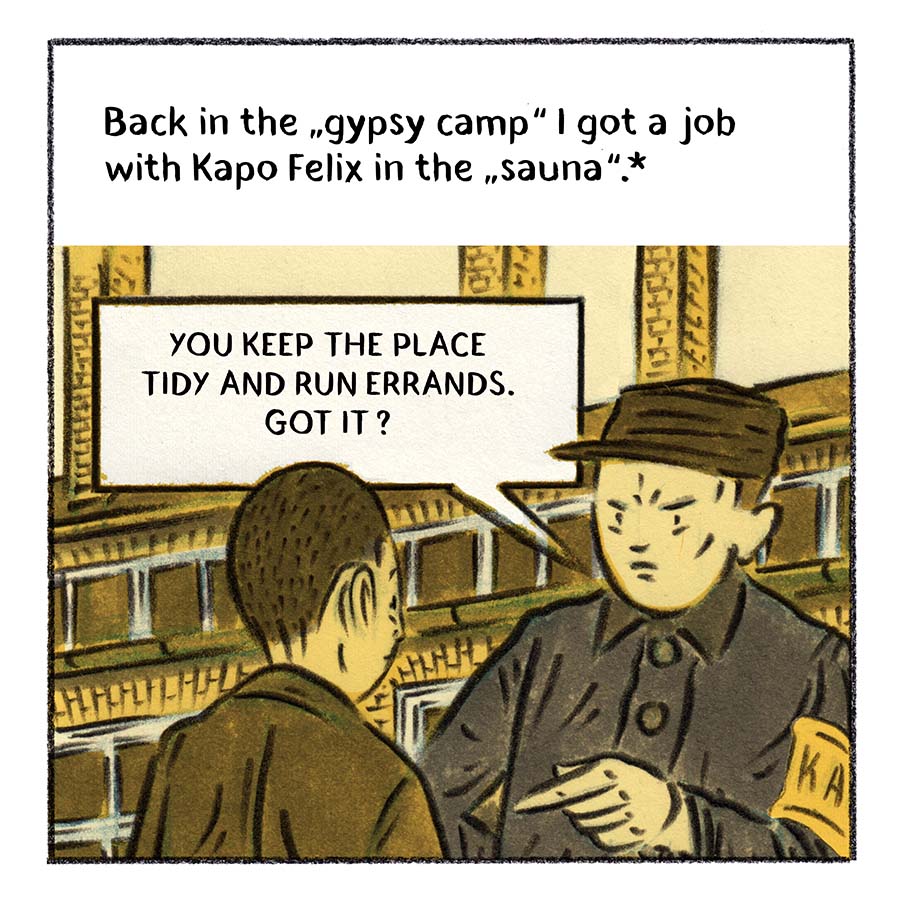

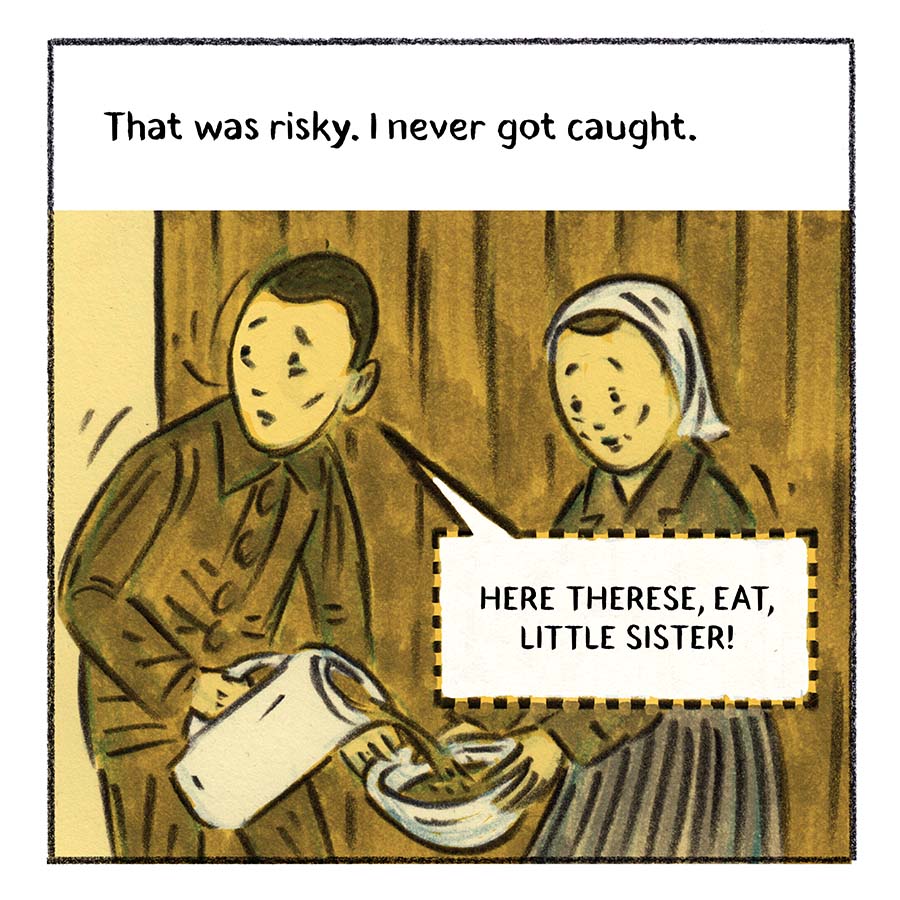

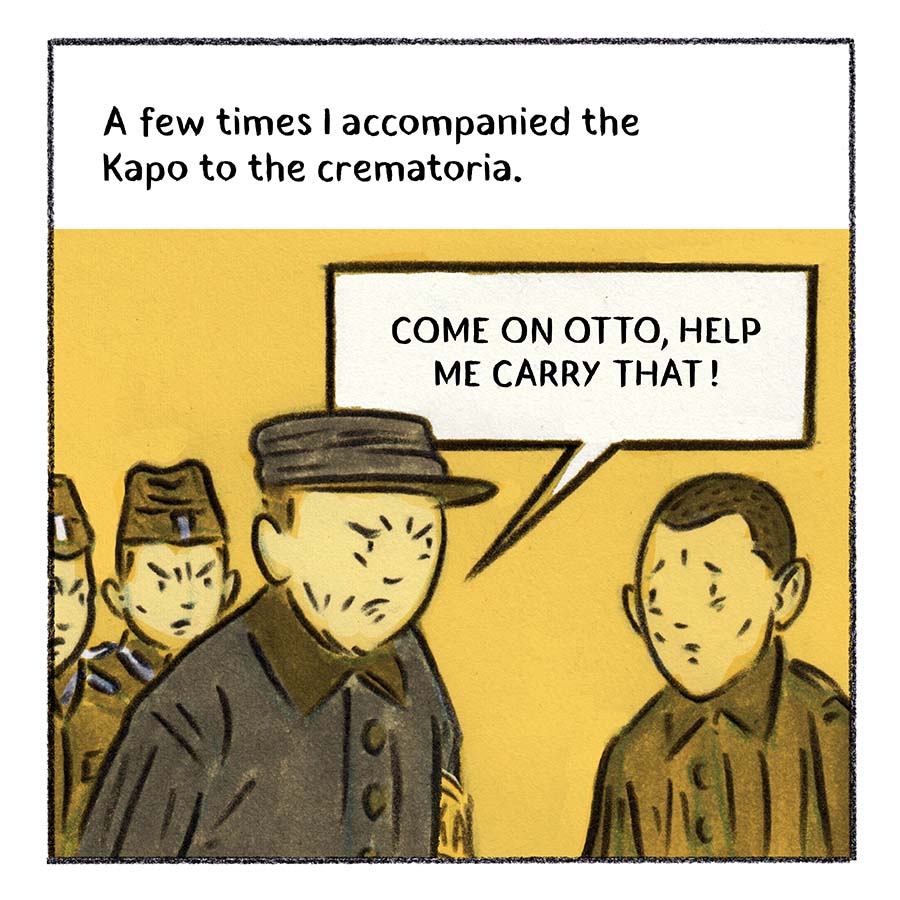

The Nazis called " prisoner functionaries" (Funktionshäftlinge) those prisoners who assisted the SS in organising work inside and outside the concentration camps and in maintaining order in the camp. As the number of concentration camp prisoners increased, they also became increasingly important for their supervision. In return, the "prisoner functionaries" (often Germans and Austrians imprisoned by the SS as "criminals") gained certain privileges. As long as they remained in favour with the SS, they had a better chance of survival than other detainees. However, they were often exposed to the hatred of their fellow prisoners because they had a great influence on the distribution of clothing and food as well as on the make-up of the work detachments (Arbeitskommandos). Functional prisoners could use their power to protect fellow prisoners, but also to assert their own interests. However, they remained prisoners themselves at all times and their survival depended on the arbitrariness of the SS.

Worn-out shoes of concentration camp prisoners in Auschwitz who did not survive the cruelty.

© Frederick Wallace, 2005

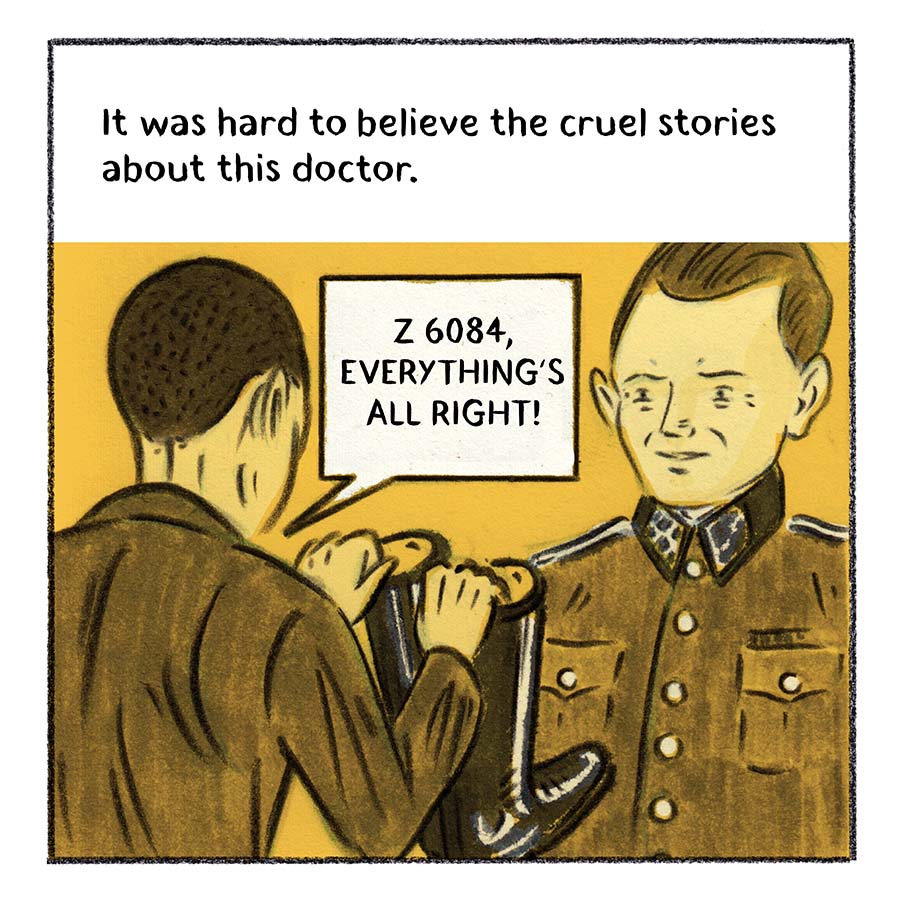

The physician and anthropologist Josef Mengele was born in 1911 in Günsburg, Bavaria. From 1937 he worked as an assistant to Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, one of the leading "racial hygienists" at the Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene (Institut für Erbbiologie und Rassenhygiene) in Frankfurt/Main, where he also earned his doctorate. In 1938 Mengele joined the NSDAP and the SS. As a battalion surgeon of the Waffen-SS, he took part in the war against the Soviet Union. In April 1943 Mengele was promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer and shortly afterwards transferred to the Auschwitz concentration camp. As camp physician of the so-called Gypsy camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau, he conducted experiments on people with physical abnormalities. He was particularly interested in heredity theories and twin research. Mengele's experiments almost always resulted in the death of his victims. When the "Gypsy camp" was liquidated in 1944, Mengele was responsible for the selection of the inmates - he sent thousands of people, including children, sick and elderly people, to the gas chambers and had around 3,000 prisoners fit for work deported to other concentration camps. At the end of the war, Mengele was briefly interned, but soon he successfully went into hiding. In 1949 he managed to escape to South America. Until 1959 he lived without being cought in Buenos Aires under a false name, later near São Paulo (Brazil). On 7 February 1979 Mengele drowned after suffering a stroke and was buried under the name "Wolfgang Gerhard". As late as 1992, a DNA analysis finally confirmed Mengele's identity beyond doubt.

Under the pretext of scientific progress, cruel, often deadly medical experiments were conducted on concentration camp inmates. Josef Mengele, camp physician at the Auschwitz concentration camp, became particularly notorious in this context. However, medical experiments were not uncommon in other concentration camps either and served a wide variety of purposes. For example, in order to assess the survival chances of German pilots shot down over the sea, prisoners were forced to drink seawater until they died of thirst due to the salt concentration in the water. In some experiments, vital organs were removed from prisoners to determine how long a person could survive without them. Open wounds of detainees were deliberately infected with staphylococci and streptococci, which often resulted in the death of the detainee as they were not given medication. Medical institutes even commissioned the murder of concentration camp inmates in order to carry out pathological experiments on the corpses.

Room for "medical" experiments, a dissection table in the Natzweiler-Struthof Concentration Camp in Alsace, France

© Sebastian Mares, 2003

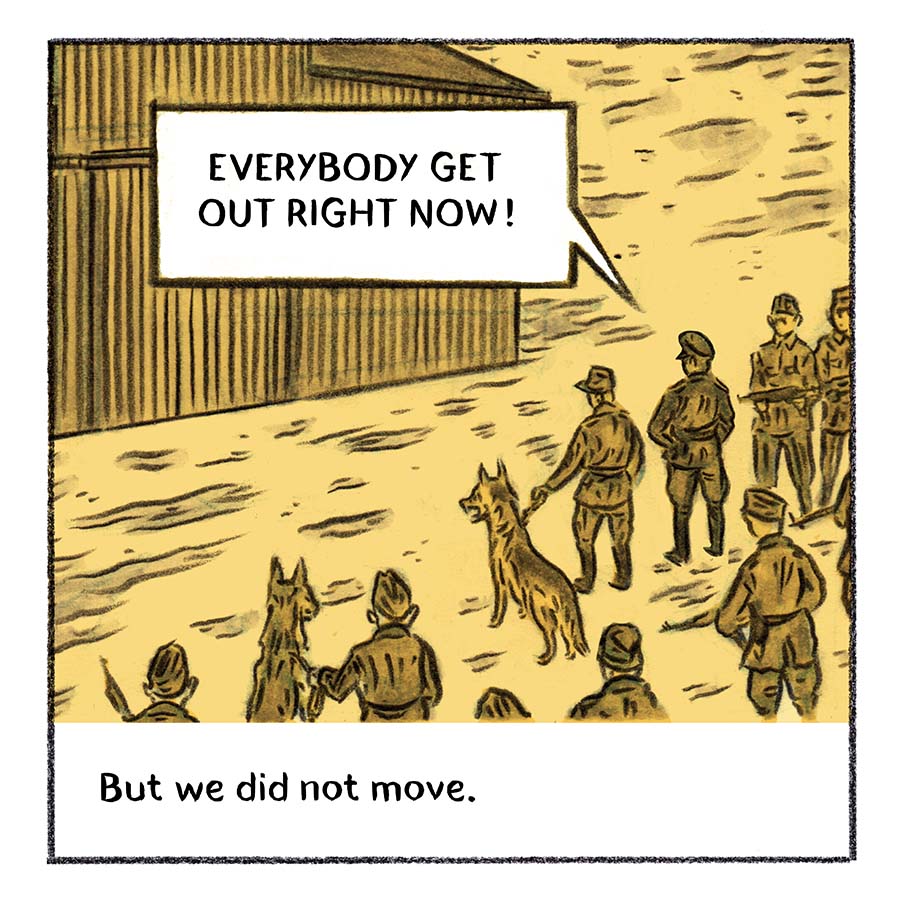

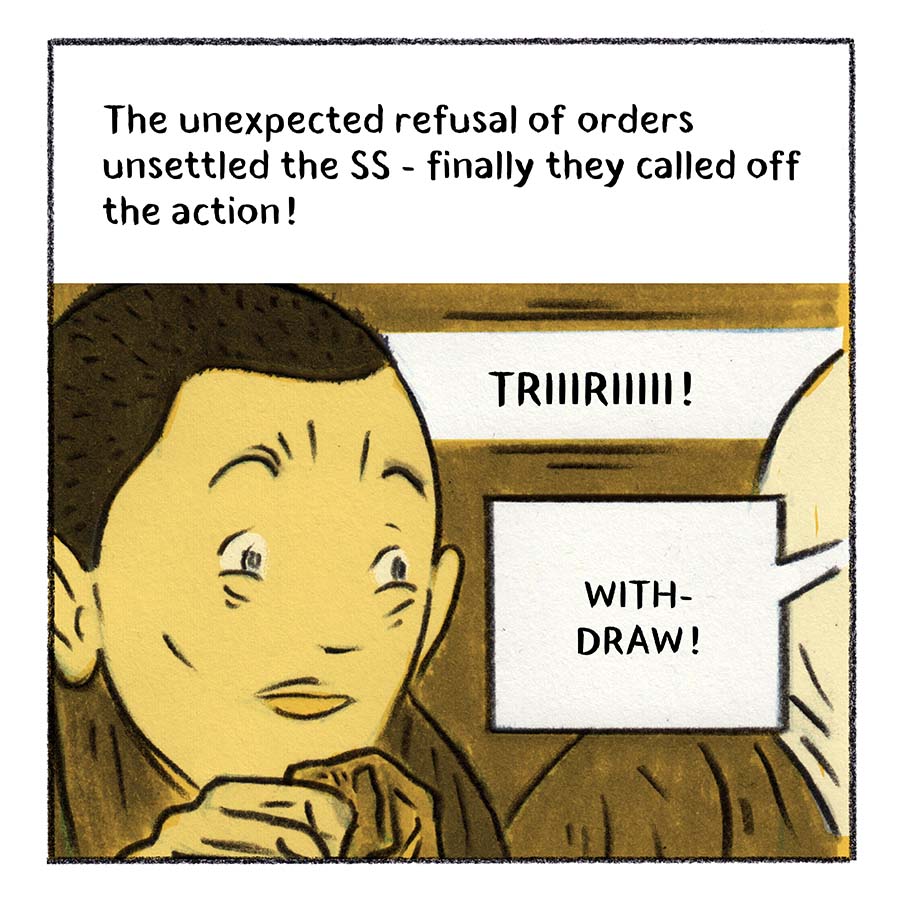

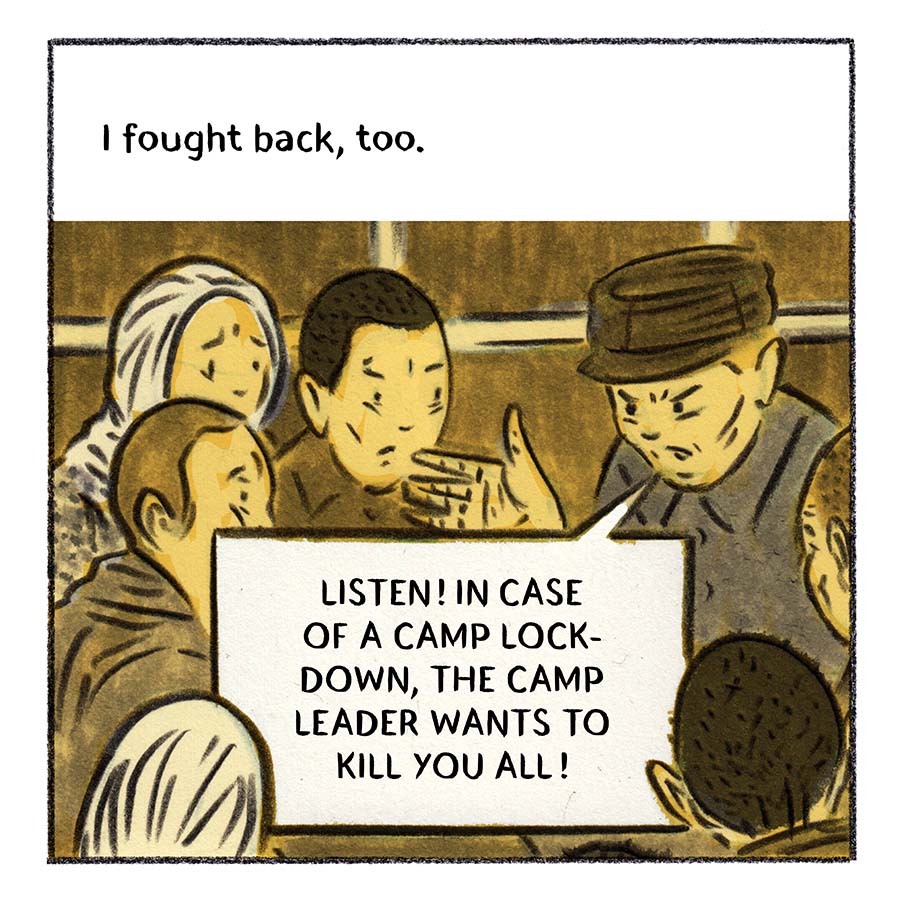

The Uprising in the "Gypsy Camp" in Auschwitz

To this day, the uprising in the so-called Gypsy camp at Auschwitz concentration camp is still little known. On 16 May 1944, imprisoned Sinti and Roma resisted their imminent murder. Armed with stones and tools, the detainees barricaded themselves inside their barracks and temporarily managed to prevent the planned liquidation of the camp, which would have meant their death. This uprising is one of the most significant acts of resistance carried out by Sinti and Roma during the Nazi regime. Despite the courageous action, the inmates were unable to prevent their extermination. When the "Gypsy camp" was liquidated in August 1944, the SS killed 2,900 of the remaining imprisoned Sinti and Roma in the gas chambers.

Path towards the Auschwitz death camp. Thousands of people had to walk along it; the prisoners in the "Gypsy camp" revolted against it in 1944.

© Krzysztof Pluta, Pixabay