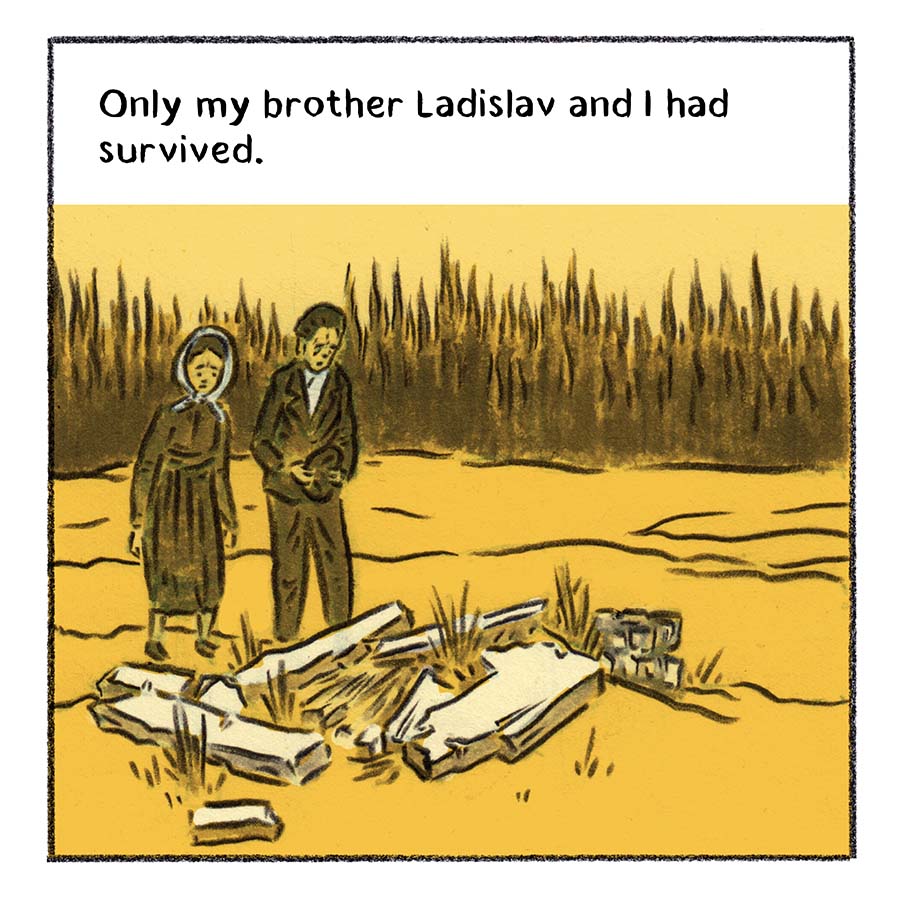

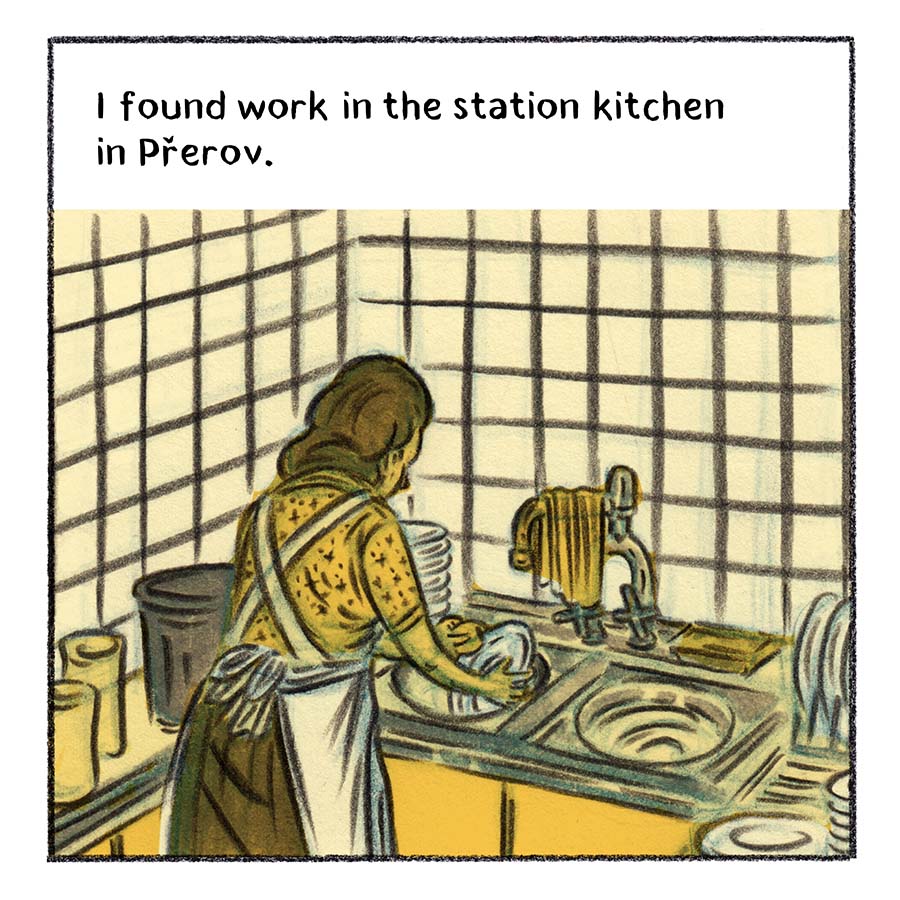

The situation of Sinti and Roma after the Second World War

After the Second World War, from the mid-1950s onwards, Communist rulers referred to Roma as a social group with a "backward way of life" that needed re-education. In 1958, the law also prohibited “vagrancy”. Starting in 1965, the communist regime began to deliberately demolish Roma settlements. As a result of this forced assimilation, many Roma no longer speak their own language, Romani. Today, Roma are still systematically discriminated against and socially excluded in the Czech Republic. Every third Roma child attends a special school for mentally disabled children - although they do not have such special needs. Officially, Roma are referred to as "socially non-adaptable citizens" in Czech political usage. Despite some concepts for Roma integration - such as the "National Action Plan for Inclusive Education" or the "Strategy for Roma Integration" - negative attitudes towards this minority are still widespread in the Czech Republic and are kept alive by local policymakers.

Discrimination against Sinti and Roma in the Czechoslovak Republic

Sinti and Roma had already been politically marginalised long before the Second World War - even the law contained various discriminatory provisions. The Czechoslovak government, for example, enacted Law 117/1927 on "Gypsies and similar work-shy vagrants" by Senate resolution of 14 July 1927. From then on, Roma could be administratively registered by means of so-called "Gypsy identity cards" and regional residence bans were issued. According to section 12 of the law, children and adolescents under 18 years of age could be placed in foster families with the purpose of their proper assimilation. After Germany's annexation of the Sudetenland and the forced signing of the "Protectorate Treaty", Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia Konstantin von Neurath upheld all discriminatory regulations against Sinti and Roma and broadened their scope in 1940 to include the immediate construction of several "Gypsy camps".

Recognition of the genocide of Sinti and Roma in Germany

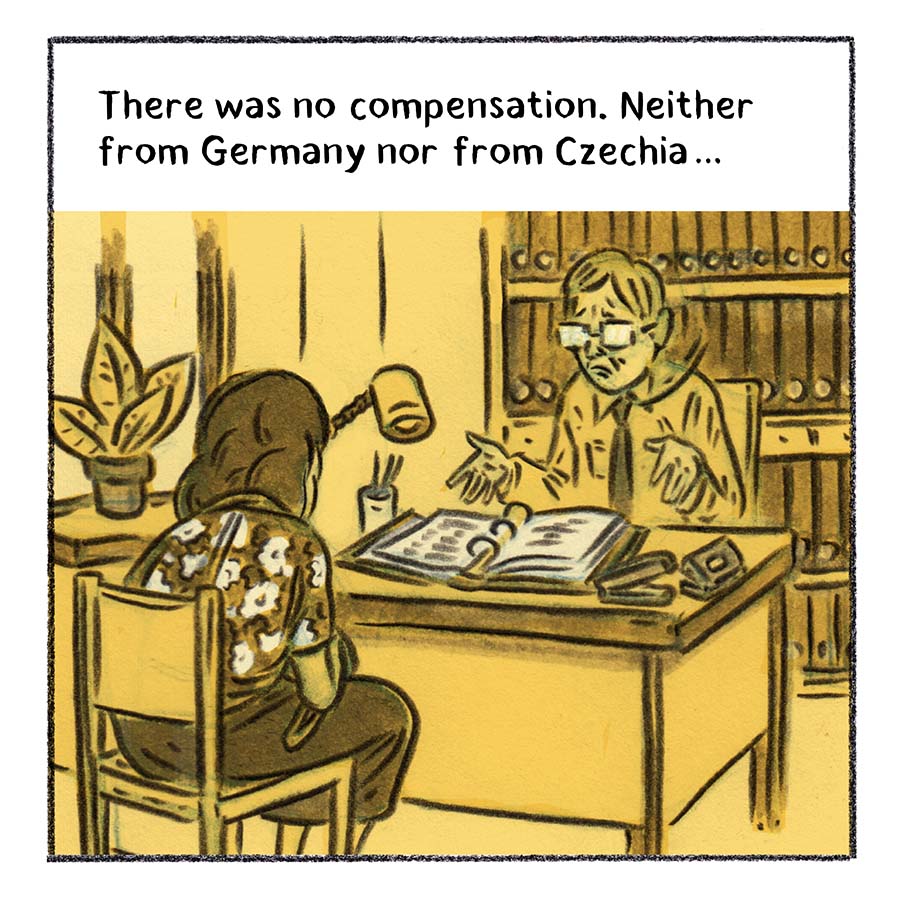

For decades after the end of the Second World War, the genocide of Sinti and Roma has not been publicly commemorated. In the Federal Republic of Germany, founded in 1949, there was no legal or moral reappraisal of the past, nor was there any material compensation for the victims. The crimes against Sinti and Roma also received little attention in the memorial sites that were being created. Recognising the need to come to terms with what happened to Sinti and Roma during National Socialism and realising that the state would not readily investigate the crimes and recognise them as victims of National Socialism, Sinti and Roma survivors of Nazi persecution organised themselves and founded the first organisations of German Sinti and Roma at the end of the 1970s. One of the pioneers of these movements was Otto Rosenberg, co-founder of the Cinti Union Berlin e.V., which later became the Landesverband Deutscher Sinti und Roma Berlin-Brandenburg e.V. (Berlin-Brandenburg Regional Association of German Sinti and Roma). In 1982, the various regional associations joined forces to form the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma. As a result of the strong regional political activism of various self-organisations and the support of the Central Council for this lobbying work, the genocide became increasingly part of the public discourse. That same year, the German government under Helmut Schmidt officially recognised the crimes committed against Sinti and Roma as genocide for the first time. Through continuous remembrance work by various associations and activists, e.g. through the exhibition at the Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma in Heidelberg, which opened in 1997, the opening of the Forced Camp Memorial Berlin-Marzahn in 2011 or the erection of the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe Murdered under National Socialism in Berlin-Mitte in 2012, the Sinti and Roma genocide during the Nazi era has gradually received more public recognition.

In 1982, the then Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt officially recognised the genocide of Sinti and Roma by the National Socialists.

Dokuzentrum Sinti und Roma, gemeinfrei

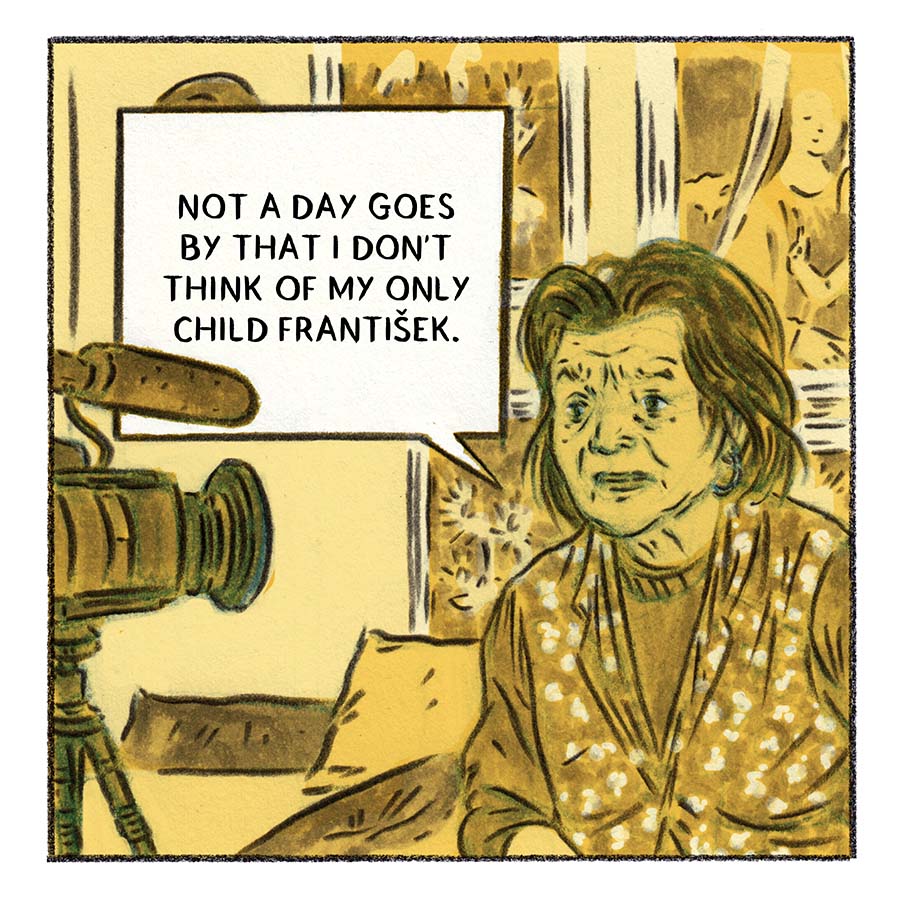

... and today? Discrimination against Sinti and Roma in the Czech Republic

A similar situation exists in the Czech Republic: a survey on minorities in the Czech Republic conducted by the Sociological Institute of the Czech Academy of Science in 2015 shows that strong prejudices against Roma still prevail and lead to them getting by far the worst rating in almost all categories surveyed - completely independent of the respondents' level of education or age. 58% of all respondents consider Roma to be extremely lazy, 82% say they do never or rarely abide by the law. At the same time, a 2018 report by the Czech government concluded that around 82% of Czech Roma are "socially excluded" and have very poor access to services, education, healthcare and work.

Roma activism in the Czech Republic and the struggle for equal rights

On the other hand, the living situation of many Sinti and Roma that is fraught with prejudice, mobilises activists in the Czech Republic who call for resistance. Today, several organisations are campaigning for the interests of the Romani people. The news portal Romea offers a comprehensive information service in Czech and English and operates its own TV channel. In addition, Roma students can apply for a scholarship. The organisation In IUSTITIA, for its part, includes lawyers and social workers and takes action against violence and hate crimes. The Romodrom Civic Association offers support in many life situations, including reintegration programmes and professional social counselling. Civil society promotes political projects such as the employment of pedagogical staff to support pupils and students in their everyday lives. Women's rights organisations are also critical of high levels of discriminationand actively oppose gender-based violence. In Prague, for instance, the international Romani cultural festival "Khamoro" has won widespread acclaim. Exhibitions, plays and concerts about the National Socialist genocide of the Sinti and Roma now also contribute to educating and informing people so that the history and fate of the Sinti and Roma becomes part of the collective memory that is passed on to future generation. The Museum of Romani Culture in Brno, founded in 1991 by Roma activists and historians, plays a major role in this process.