After the Second World War, from the mid-1950s onwards, Communist rulers referred to Roma as a social group with a "backward way of life" that needed re-education. In 1958, the law also prohibited “vagrancy”. Starting in 1965, the communist regime began to deliberately demolish Roma settlements. As a result of this forced assimilation, many Roma no longer speak their own language, Romani. Today, Roma are still systematically discriminated against and socially excluded in the Czech Republic. Every third Roma child attends a special school for mentally disabled children - although they do not have such special needs. Officially, Roma are referred to as "socially non-adaptable citizens" in Czech political usage. Despite some concepts for Roma integration - such as the "National Action Plan for Inclusive Education" or the "Strategy for Roma Integration" - negative attitudes towards this minority are still widespread in the Czech Republic and are kept alive by local policymakers.

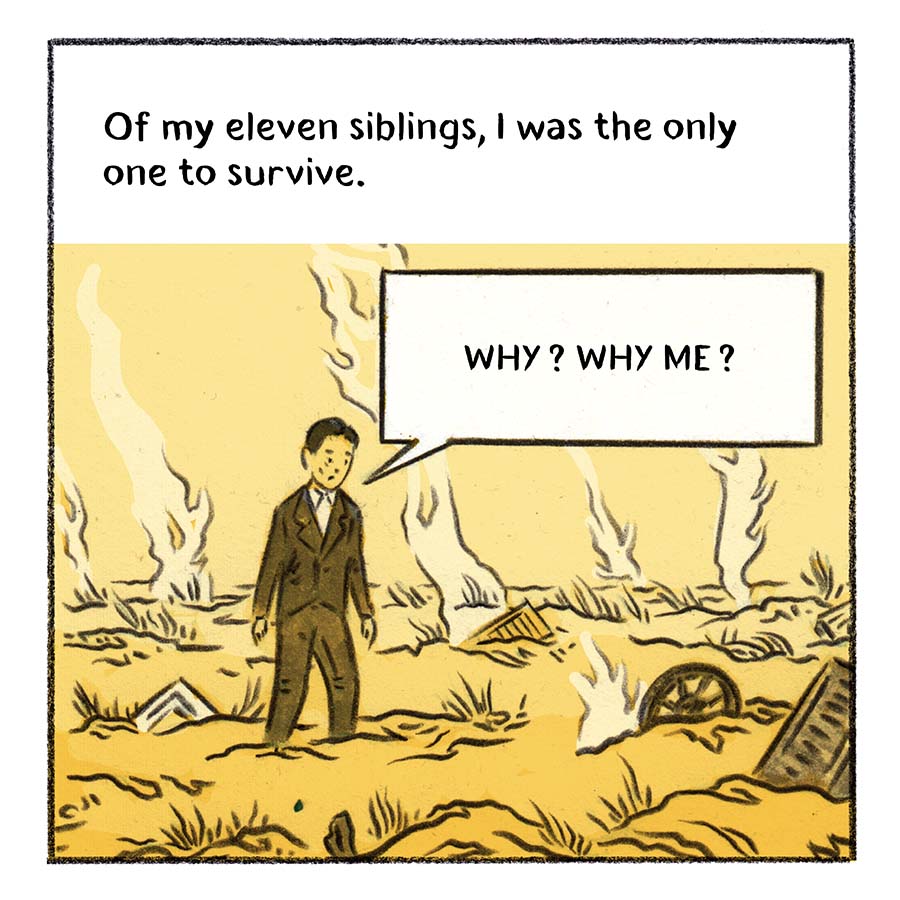

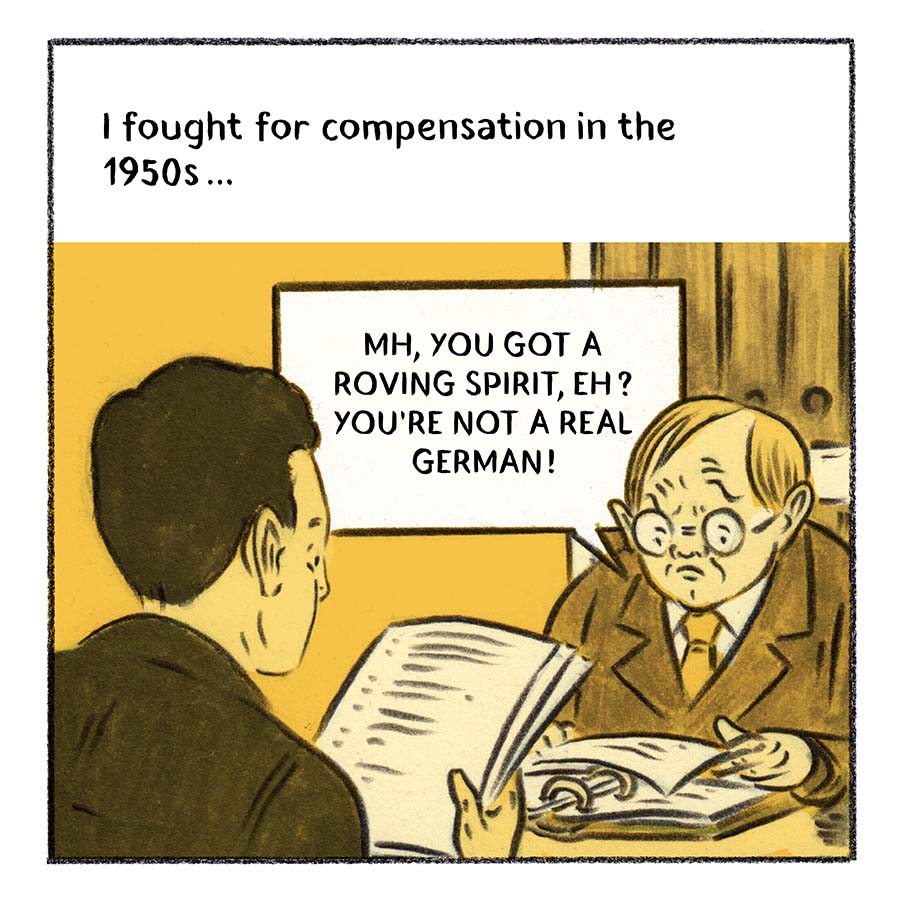

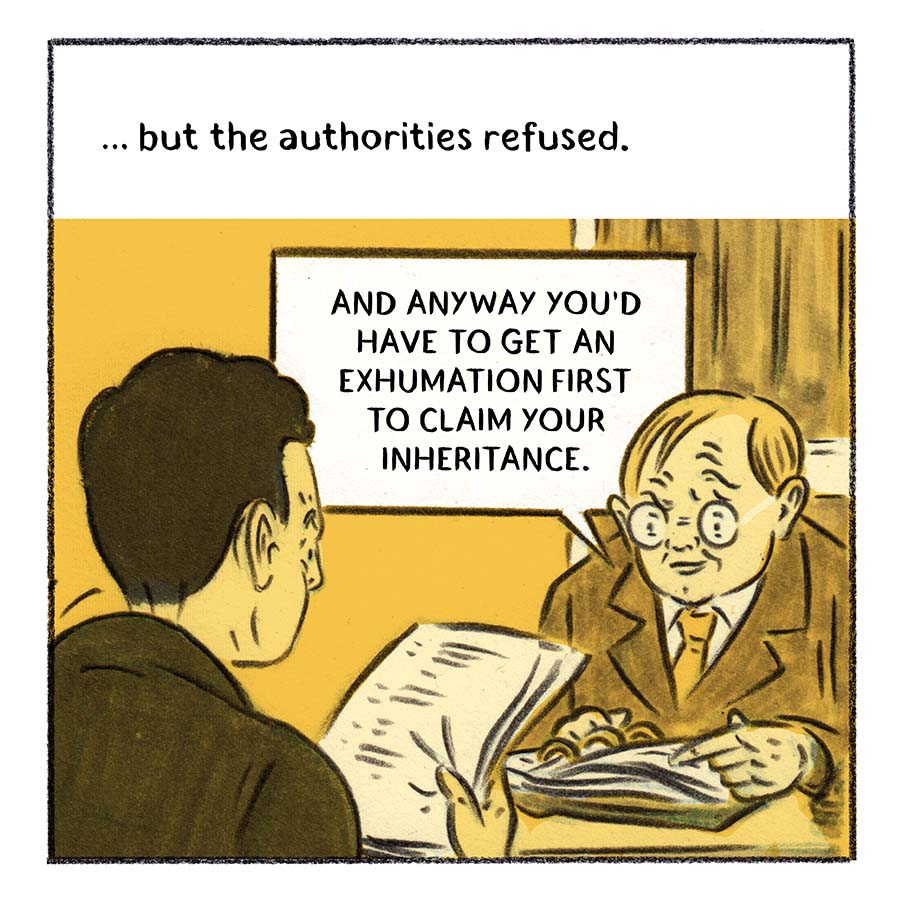

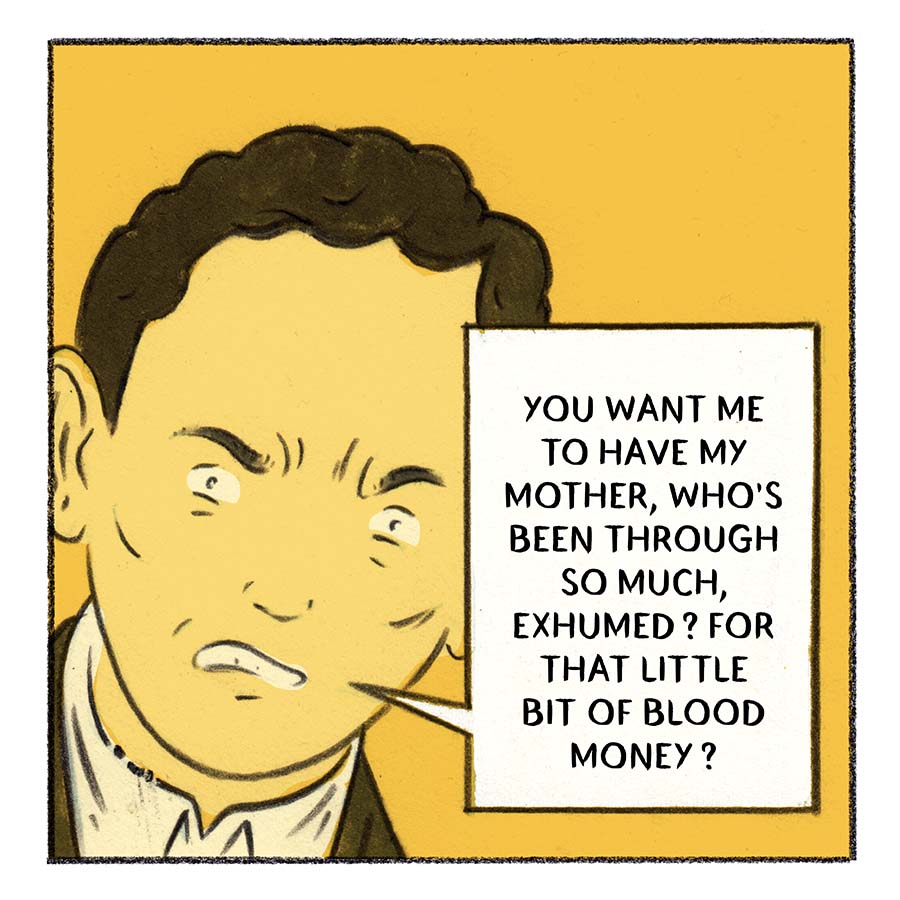

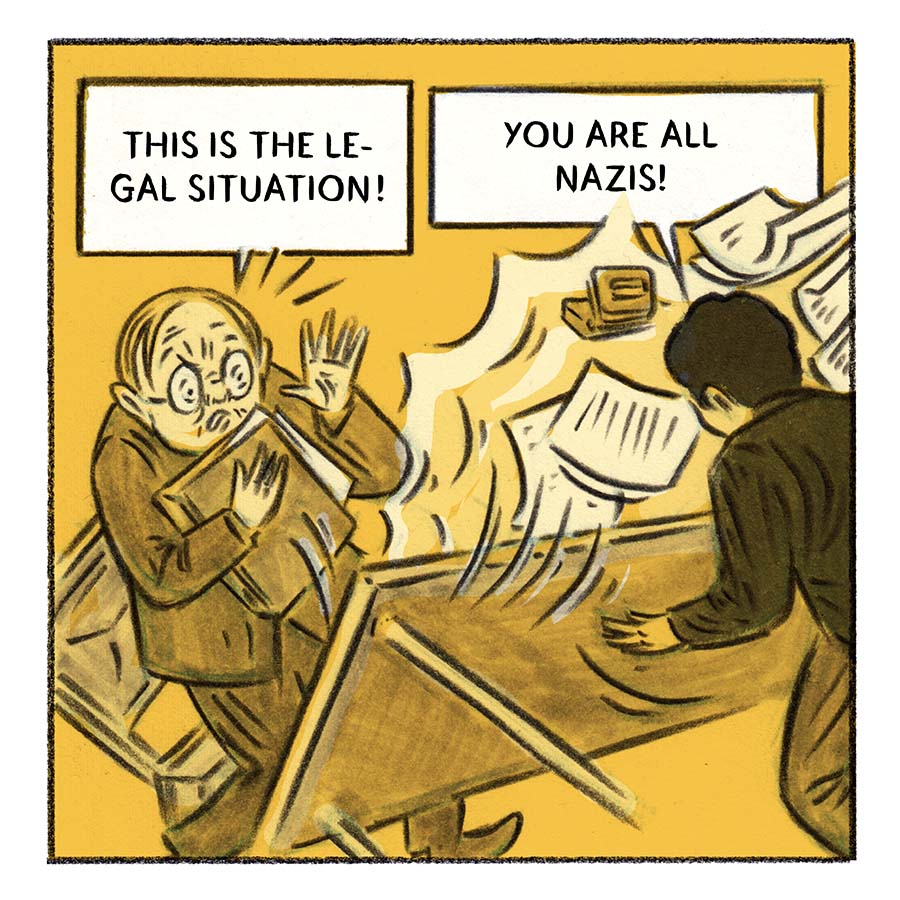

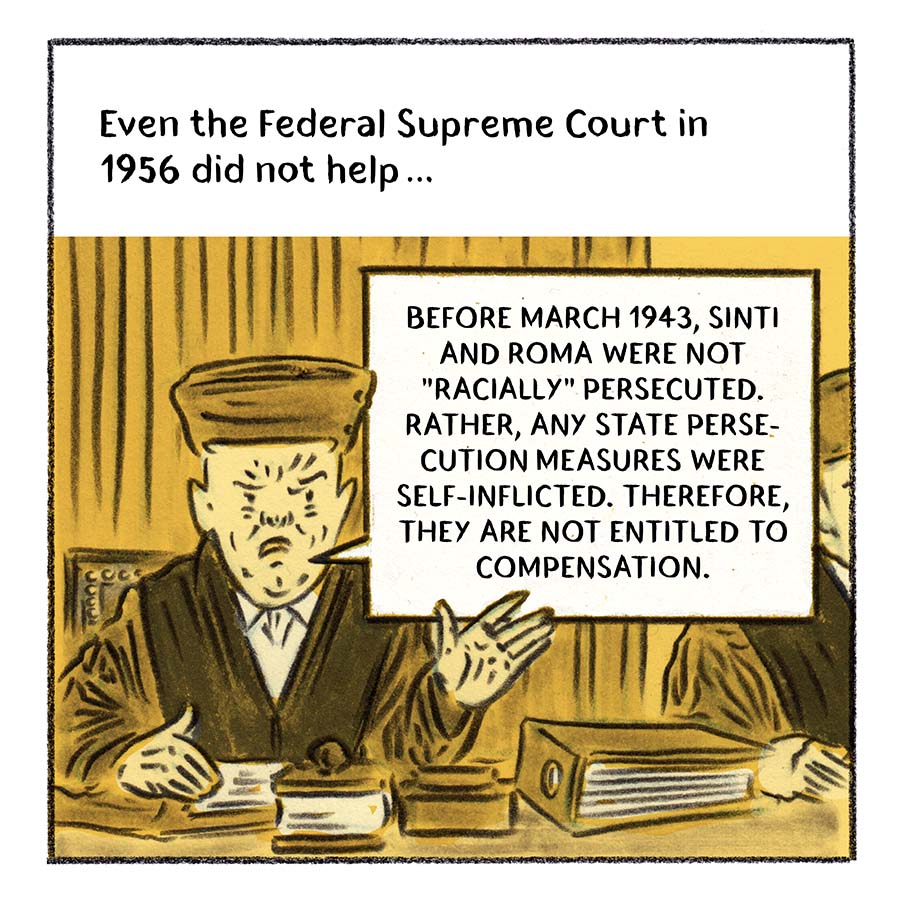

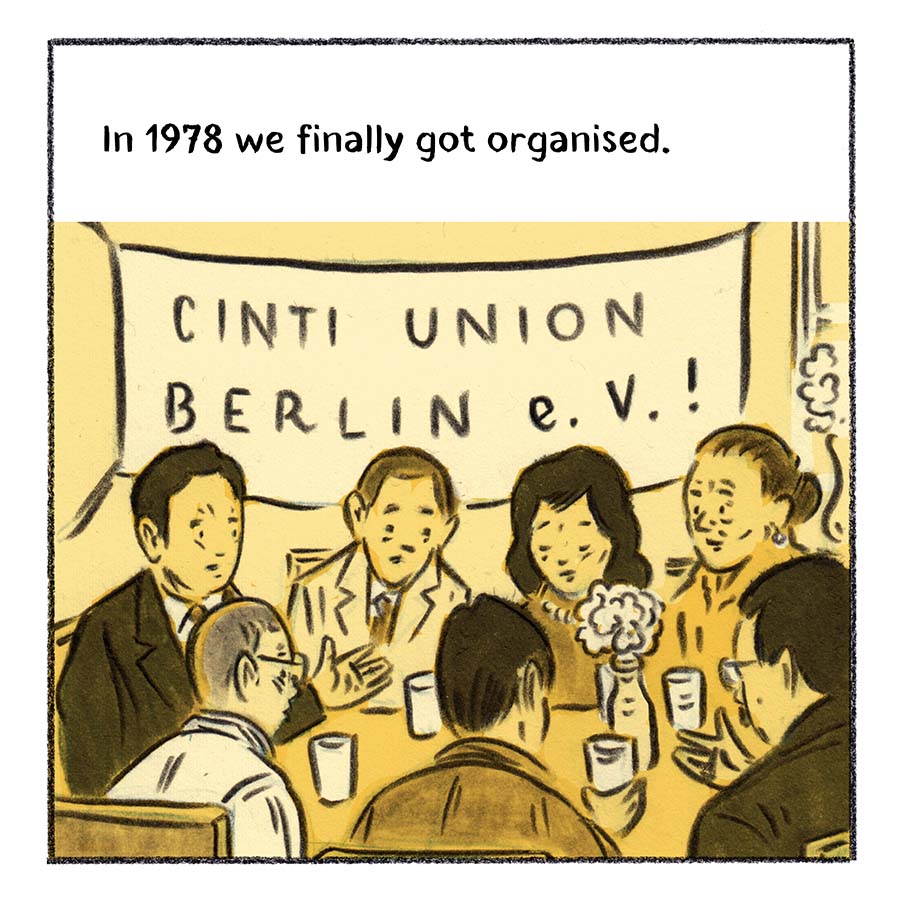

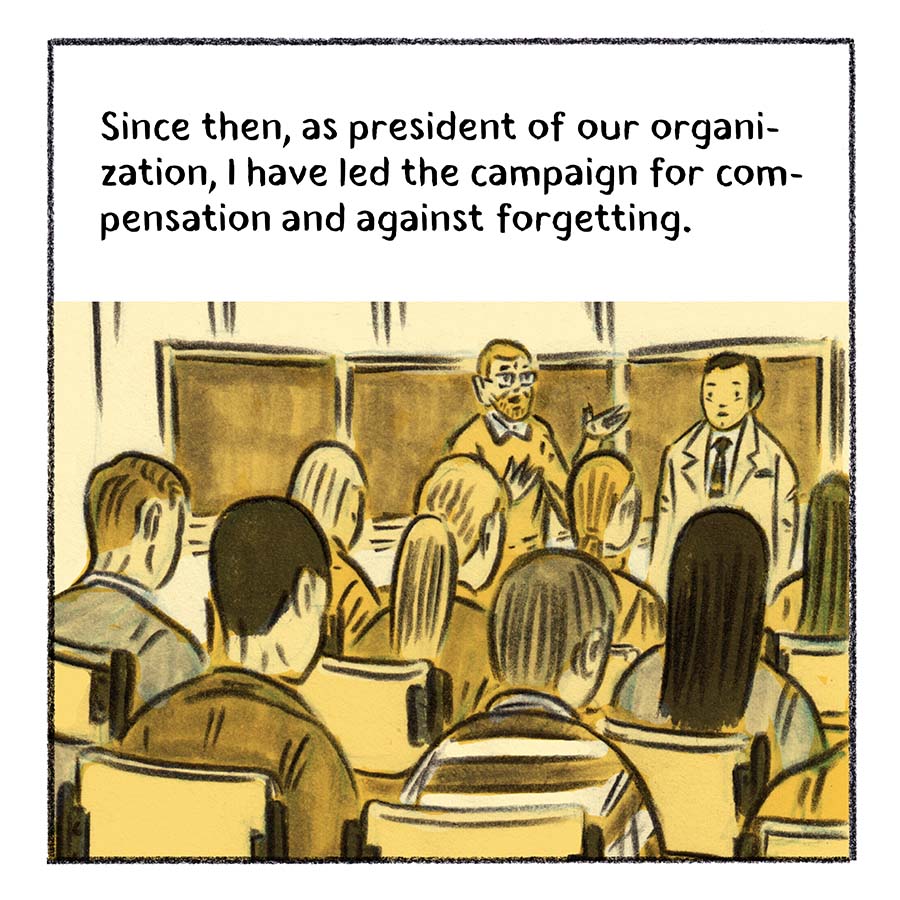

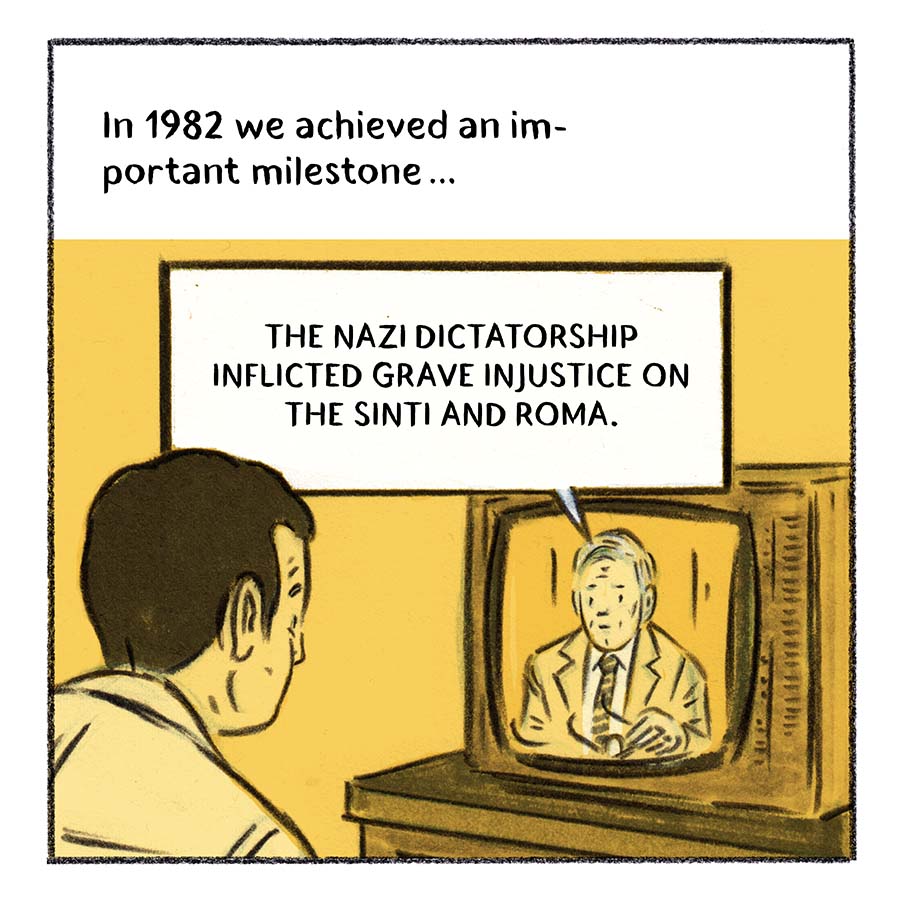

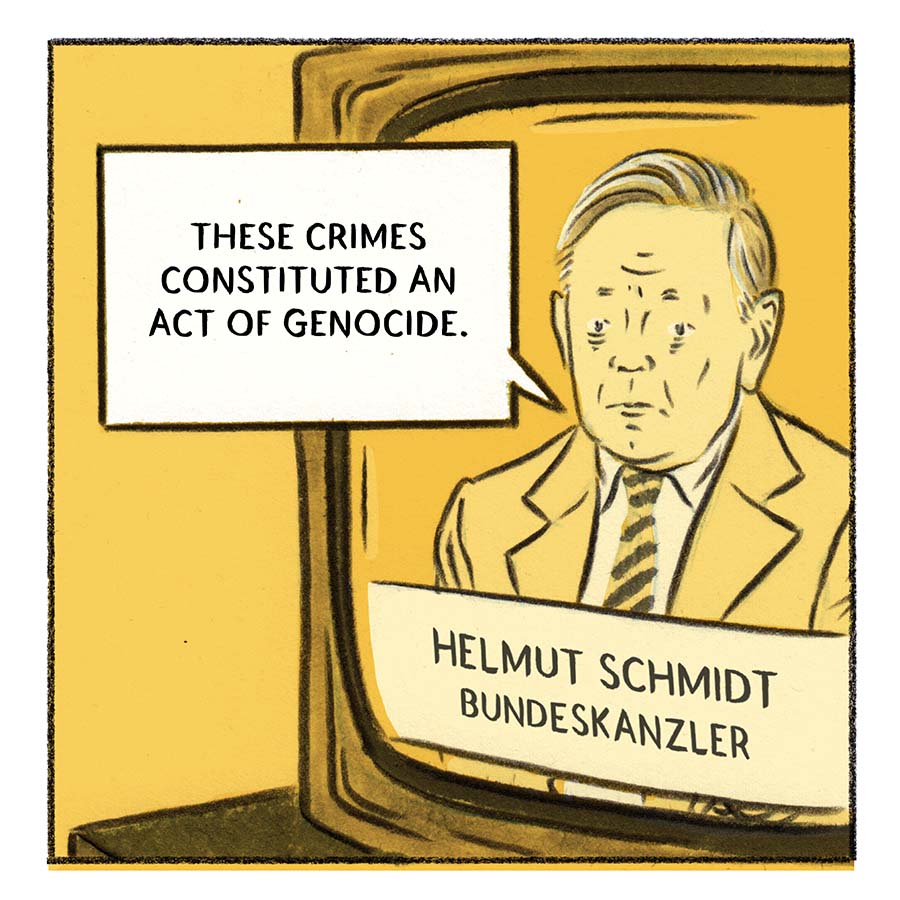

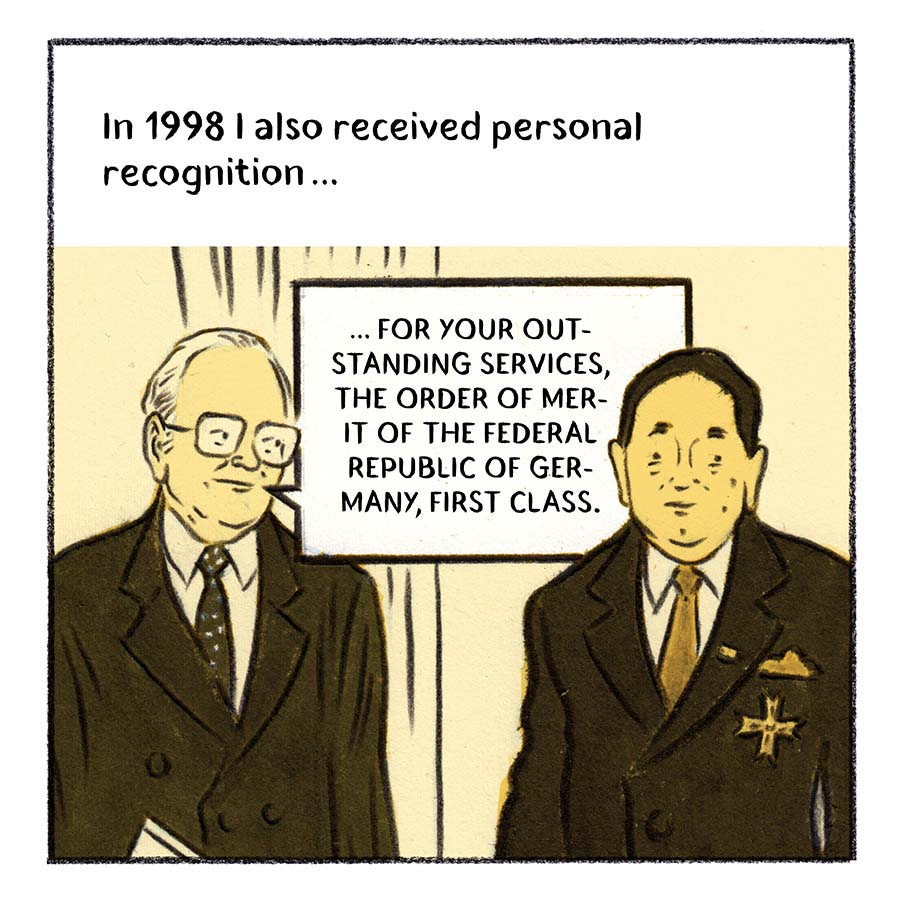

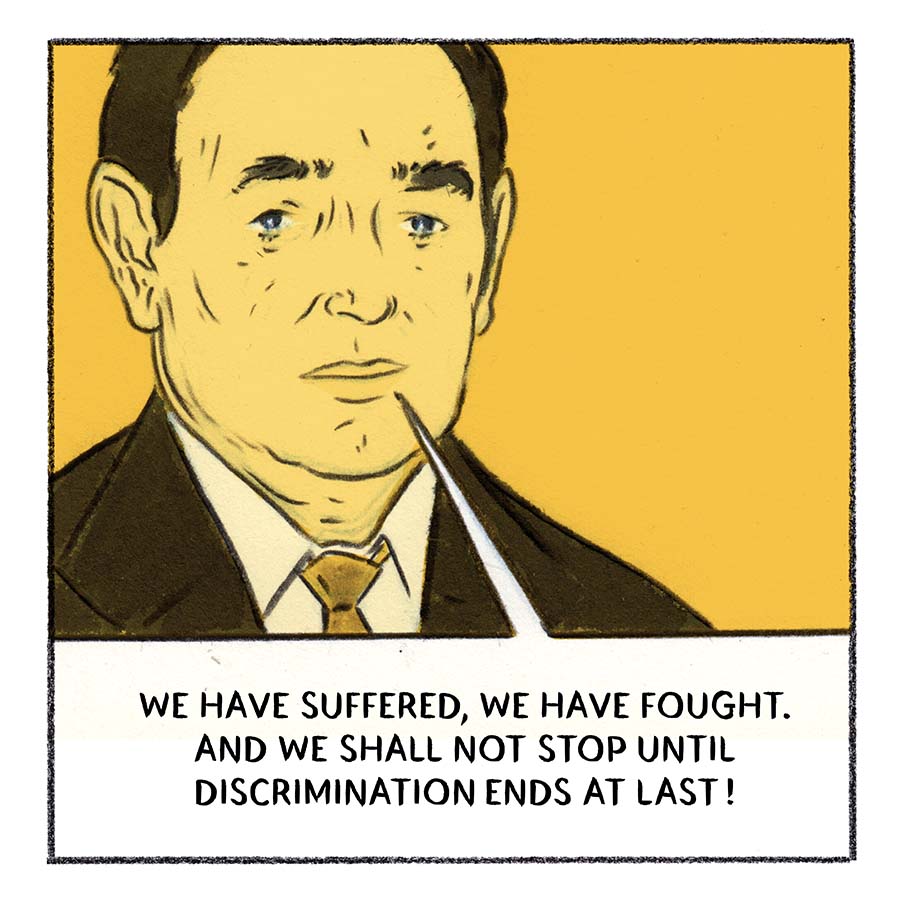

For decades after the end of the Second World War, the genocide of Sinti and Roma has not been publicly commemorated. In the Federal Republic of Germany, founded in 1949, there was no legal or moral reappraisal of the past, nor was there any material compensation for the victims. The crimes against Sinti and Roma also received little attention in the memorial sites that were being created. Recognising the need to come to terms with what happened to Sinti and Roma during National Socialism and realising that the state would not readily investigate the crimes and recognise them as victims of National Socialism, Sinti and Roma survivors of Nazi persecution organised themselves and founded the first organisations of German Sinti and Roma at the end of the 1970s. One of the pioneers of these movements was Otto Rosenberg, co-founder of the Cinti Union Berlin e.V., which later became the Landesverband Deutscher Sinti und Roma Berlin-Brandenburg e.V. (Berlin-Brandenburg Regional Association of German Sinti and Roma). In 1982, the various regional associations joined forces to form the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma. As a result of the strong regional political activism of various self-organisations and the support of the Central Council for this lobbying work, the genocide became increasingly part of the public discourse. That same year, the German government under Helmut Schmidt officially recognised the crimes committed against Sinti and Roma as genocide for the first time. Through continuous remembrance work by various associations and activists, e.g. through the exhibition at the Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma in Heidelberg, which opened in 1997, the opening of the Forced Camp Memorial Berlin-Marzahn in 2011 or the erection of the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe Murdered under National Socialism in Berlin-Mitte in 2012, the Sinti and Roma genocide during the Nazi era has gradually received more public recognition.

In 1982, the then Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt officially recognised the genocide of Sinti and Roma by the National Socialists.

Dokuzentrum Sinti und Roma, gemeinfrei

... And today? Discrimination against Sinti and Roma in Germany

The cultural, social and economic situations of Sinti as well as Roma are just as heterogeneous as those of the majority society. They differ in terms of family and individual circumstances, regional contexts, social class and education. Nevertheless, Sinti and Roma are regularly perceived as a homogeneous group. Prejudices and the inevitably associated racist exclusion and discrimination are unfortunately still part of their everyday life. This also includes discrimination in the housing and labour markets, often resulting in Sinti and Roma concealing their identity. Such resentments are rarely critically examined and challenged. Unfortunately, the media also contribute to the perpetuation of old stereotypes through their partially prejudiced reporting.